[Donald Worster, Historian] The biggest percentage of people who moved into another state were going to California. There were hundreds and hundreds of thousands of people pouring into California. They weren't all poor, and they weren't all from the Great Plains. So there was a river of people flowing into California in the 1930s. You could just see all of these cars pulling out from little side roads along the way joining this brigade going out Route 66, stopping at motels, sleeping under billboards. that's the way my parents essentially went from New Mexico across to Arizona.

NEXT TIME TRY THE TRAIN: SOUTHERN PACIFIC. TRAVEL WHILE YOU SLEEP.

They stopped in Needles, California, and didn't get any farther. That was the end of the road for them.

[Narrator] Those who did leave the Dust Bowl for California were joining an even larger exodus of Americans displaced by the Depression and the agricultural crisis that extended far beyond the Southern Plains.

[Timothy Egan, Writer] Now, the folks who left, the diaspora, the Exodusters, they were called -- these refugees were largely from the Eastern fringe of the Dust Bowl. They were from arguably not even the Dust Bowl itself. They were Arkies from Arkansas. They were from Missouri. And they were tenant farmers. When the farm economy collapsed, when the prices collapsed and you couldn't make a living, if you were a tenant farmer, you had nothing, because you didn't even own the dirt. So they left.

[Woody Guthrie] These people didn't have but one thing to do, and that was to just get out in the middle of the road. These people just got up, and they bundled up their little belongings, they throwed in one or two little things they thought they'd need, had heard about the land of California, and according to the handbills they passed out down in that country, you're supposed to have a wonderful chance to succeed in California.

[Woody Guthrie] [Singing]

I'm blowing down this old dusty road

I'm blowing down this old dusty road

I'm blowing down this old dusty road, lord, lord

And I ain't gonna be treated this way

[Narrator] Back in Colorado, with the money from selling his horses in his pockets, Calvin Crabill's father loaded what he could into their sedan and a little two-wheeled trailer, and joined the stream of cars rattling down Highway 66, with his 11-year-old son and asthmatic wife.

[Calvin Crabill, Prowers County, CO] When you came down that grade in San Bernardino, my mother, she was so happy, and you saw the green valley there -- that was a beautiful, beautiful sight. You see the trees. You see the trees. So my mother that day picked an orange, a ripe orange, and ate it, and that was something for her.

[Donald Worster, Historian] The migration out of the Great Plains in the 1930s was one of the biggest folk migrations in American history. It dwarfs the movement along the Oregon trail in the 19th century, the covered wagon era, which we've so idealized and romanticized. But we've forgotten this migration of the 1930s. Nobody celebrates it. There are no California Trail associations. We're ashamed of it, basically, because it was a migration of the defeated.

[Narrator] Out in Oakland, California, Harry Forester, who had left his family in Goodwell, Oklahoma, was now working a variety of jobs, sometimes making a dollar a day and sending as much of it as possible back to his ailing wife and children. Everything he held dear was half a continent away. The separation from his family made him miserable, and then came news from home that added to his woes -- one of his five sons, Slats, had come down with dust pneumonia.

[Louise Forester Briggs, Texas County, OK] My oldest brother god dust pneumonia, was at death's door, and my dad didn't know whether to come home or not because he thought he was gonna die. I imagine he was absolutely the loneliest man on the planet.

[Narrator] Forester decided his family should join him in Oakland as soon as they could.

Back in Goodwell, the Forester children mobilized for the move. They added hoops and tarps and a hand-built box for storing and serving food to a 1928 Chevy truck, converting it into a modern-day covered wagon. But Mrs. Forester's aged and blind mother refused to leave, so Slats, who had recovered, was left behind to care for her. They made their goodbyes, and brother Clois took the wheel with his frail mother in the front seat next to him. Then the other seven Forester children scrambled aboard, and they set off for California.

[Louise Forester Briggs, Daughter, Texas County, OK] It was pretty exciting for me because it was hope ... in a hopeless little heart. We were going to California and have oranges and stuff, you know? And we would have fruit, and we would live happily. And it was just an exciting time. I just couldn't wait to get there.

[Shirley Forester McKenzie, Daughter, Texas County, OK] We sat in different places. We'd move around. The mattresses were rolled up, and stuffed in the truck bed, so we had those soft mattresses to sleep on.

[Louise Forester Briggs, Daughter, Texas County, OK] And my favorite spot seemed to be right over the wheel of the truck. And we had the side tarps rolled up so you could see out. And one thing I remember, I was so glad -- we saw a weeping willow tree, and I'd never seen one.

[William Forester, Son, Texas County, OK] My brother was obsessed with the potential that we might run out of gas, so he stopped at damn near every gas station to top off the tank. It was a little four-banger Chevy, and he drove it at about maximum of 35 miles an hour, and it took a long time.

[Robert Forester, Son, Texas County, OK] He had a goal in mind and that was to get this crew safely through. He was a nervous Nelly anyway, and he had lots of tribulations when he had to take this job -- well, because it was a big job. He's a 21-year-old guy, and he's taking his sick mother and a bunch of kids all the way to California, across that big ol' desert. It was a ... a real worry for him, I know.

[Narrator] They were all anxious about their mother's fragile health, which prompted them to stop a number of times so she could recoup her strength, especially when a dust storm overtook them in New Mexico.

[William Forester, Son, Texas County, OK] And she was worn down by the travails of the previous years, and she was just in bad shape, and she was very feeble all along the way. Instead of camping one night in New Mexico, we used a little of our scarce money to rent a motel so that she could be sleeping out of the dust.

[Narrator] But in Eastern Arizona, despite her condition, she insisted that Clois detour through the Painted Desert and Petrified Forest, which she had always yearned to see.

[William Forester, Son, Texas County, OK] My mother's health got worse after that. We felt that it was necessary to just stop and not travel so that she could have time being still and resting in a cool, shaded place.

[Narrator] Farther on, they had to descend to the Colorado river on a winding road unlike anything on the Southern Plains.

[Louise Forester Briggs, Daughter, Texas County, OK] But I had a great disappointment when we went and hit the California border down at Needles. [Laughing] You're in the desert, and I felt, oh ..., I just went, "Oh, my God, no," because I was just broken-hearted, because I thought there'd be orange groves right there, you know.

[Narrator] They crossed the Mojave Desert at night, then turned north, up the Central Valley, and finally made it to Oakland, on the moist San Francisco Bay, where Harry Forester had rented a house, and was waiting anxiously for them to arrive.

[Louise Forester Briggs, Daughter, Texas County, OK] And we got into Oakland, and we went to Lake Merritt, and went up Grand Avenue, and turned right on Moraga and went up Moraga Avenue. We're in the hills now, in the Oakland Hills, which are pretty steep for someone like us.

[William Forester, Son, Texas County, OK] When we stopped in the canyon, telephoned that we were coming up the road, we were a mile and a half from the house, we started driving, and dad started hustling, and he raced down to the bottom of the canyon so that he was standing beside the road as we came driving by ten minutes later.

[Louise Forester Briggs, Daughter, Texas County, OK] And my dad met us at the corner of Pine Haven Road and Heather Ridge Way, and he had a house rented on the corner just up the corner a ways. I remember sitting in the back of the truck waiting for my dad to come and greet us while he was greeting mom and my brother and whoever had been riding with them.

[William Forester, Son, Texas County, OK] And he went around to the back, and he took each of the kids in turn, and he gave us a hug, and we laughed, [choking up] and it was great.

[Louise Forester Briggs, Daughter, Texas County, OK] And then he came around back and started lifting us out one at a time and giving us a hug and putting us down. And I looked around, and I thought, "Oh, yes, we have come to Canaan Land."

[Narrator] Then Harry Forester, who had once dreamed of amassing so much land he could bestow each of his sons with one square mile of rolling Oklahoma prairie, showed them all their new home -- a rented house of three rooms, on a hill so steep the buildings needed stilts to be level.

[Robert Forester, Son, Texas County, OK] And there were big pine trees -- oh, 60-, 70-foot, 80-foot tall, big trees, and that was spectacular. It wasn't Oklahoma, you know? [Laughing] Toto, we aren't in Oklahoma anymore. [Laughing]

[Shirley Forester McKenzie, Daughter, Texas County, OK] [Laughing] Especially to a fair-skinned, freckle-faced, red-headed youngster that I was, where that hot wind always just burned me. The mist and the rain was so light often that we kids would go off to school that first year without a hat or a coat or anything, because we just loved the feeling of that moisture on us. We were parched, too.

[Wayne Lewis, Beaver County, OK] There weren't any crops. It was dry, and so we didn't get any crops. One of those years, we put our entire wheat crop in one wagon, which was maybe 50 bushels.

[Clarence Beck, Cimarron County, OK] They were good people. There was nothing about the population that was bad. Everybody was hard-working, trying to make an honest living, and nature just wouldn't let them do it. So there were failures, and there were also people that were awful hard to knock off of the bush. And it ended up, a Depression, the Dust Bowl didn't get them all. It left quite a few. But it left the hardy ones.

[Pauline Durrett Robertson, Potter County, TX] Oh, there were many jokes about the dust, of course. So that we laughed so we wouldn't cry, I guess. One of them was, a rancher, after a big dust storm, walked out to see about his land, and he was trying to find the barbed-wire fence that had been covered with dirt. But he saw the tops of it, and there was the cowboy's hat over there. So he walked over and picked up the cowboy's hat, and underneath was a cowboy. And he said, "Oh, my goodness. Aren't you in trouble there?" He's covered with dust. And he said, "Well, I think I'm gonna be okay, but this horse I'm riding is in a little trouble."

[Narrator] By now, those who remained in the Dust Bowl had found that one way to deal with what was happening to them was to poke fun at it.

[Robert "Boots" McCoy, Texas County, OK] Well, there's an old saying there that one of the old-timers was telling the people that they'd had a chain wrapped around a corner post, and said when that chain got sticking out straight, that was a pretty good wind, but when it went to snapping the links off, it was damn windy. [Laughing] Of course, that wasn't true. That was just a saying. [Laughing]

[Narrator] 1936 would prove to be as dry as 1935, with even more dust storms. In April, an outsider showed up in Boise City. Arthur Rothstein was 21 years old, the son of Jewish immigrants, born and raised in New York City. He was in No Man's Land to take photographs for the federal government's resettlement administration. Rothstein's boss, Roy Stryker, believed that pictures could be a powerful tool to show not only the multitude of problems the nation was facing, but what the government was doing about them. Over the course of seven years, as the Agency became part of the Farm Security Administration, Stryker would launch an unprecedented documentary effort, eventually amassing more than 200,000 images of America in the 1930s, taken by a talented cadre of photographers, including Walker Evans, Russell Lee, Marion Post Walcott, John Vachon, and Dorothea Lange.

[Timothy Egan, Writer] And he sent them out there with a very simple set of instructions -- I want to see their eyes. I want to see their faces. I want to see emotion. I want people to look at these pictures and not see abstraction. I want them to see folks struggling in the land.

[Narrator] Prior to arriving in Oklahoma, Arthur Rothstein's assignment had taken him on a nationwide tour of the Depression. He had documented rural people being dispossessed to create Shenandoah National Park, desperate tenant farmers in Arkansas, hard-luck ranchers in Montana, and slum dwellers in St. Louis. But the most distressing situation he ever encountered, he remembered later, was what he saw driving through the Dust Bowl. "It was like a landscape of the moon," he said, populated by "hard-working people who, through no fault of their own, needed assistance, and the only place they could get that assistance was from the government."

About fourteen miles south of Boise City, he came across Art Coble, digging out a fence post from a sand drift. Rothstein chatted with him and his two young sons, snapped a few pictures, and was getting back into his car when the wind suddenly picked up. Looking back, he saw them bending into the storm, pointed his camera at them, and clicked the shutter. The image that Rothstein captured touched emotional chords with everyone who saw it, becoming the iconic picture of the Dust Bowl, and one of the most widely reproduced photographs of the 20th century.

In addition to hiring photographers, the federal government also underwrote a documentary film, and that summer it premiered at the Mission Theatre in Dalhart, Texas. "The Plow That Broke the Plains," directed by Pare Lorentz, was meant to describe the causes of the Dust Bowl and what Roosevelt's New Deal was trying to do about it.

[Film Narrator] The grasslands -- a treeless, windswept continent of grass ... a country of high winds and sun, high winds and sun.

THE PLOW THAT BROKE THE PLAINS

written and directed by Pare Lorentz

[Transcribed from the movie by Tara Carreon]

PROLOGUE: This is a record of land, of soil, rather than people -- a story of the Great Plains: the 400,000,000 acres of wind-swept grass lands that ...

spread up from the Texas panhandle to Canada. A high, treeless continent, without rivers, without streams. A country of high winds, and sun, and of little rain.

By 1880, we had cleared the Indian, and with him the buffalo, from the Great Plains, and established the last frontier. A half million square miles of natural range.

This is a picturization of what we did with it.

THE PLOW THAT BROKE THE PLAINS

A U.S. DOCUMENTARY FILM

COPYRIGHT MCMXXXVI BY PARE LORENTZ -- RESETTLEMENT ADMINISTRATION

WESTERN ELECTRIC NOISELESS RECORDING

RECORDED BY EASTERN SERVICE STUDIOS, NEW YORK, N.Y.

WRITTEN AND DIRECTED BY PARE LORENTZ

PHOTOGRAPHY: RALPH STEINER; PAUL IVANO; PAUL STRAND; LEO T. HURWITZ

MUSIC: COMPOSED BY VIRGIN THOMSON; CONDUCTOR: ALEXANDER SMALLENS

NARRATOR: THOMAS CHALMERS

RESEARCH EDITOR: JOHN FRANKLIN CARTER, JR.

FILM EDITOR: LEO ZOCHLING

SOUND TECHNICIAN: JOSEPH KANE

[GREAT PLAINS AREA

MONTANA; N. DAKOTA; WYOMING; S. DAKOTA; NEBRASKA; COLORADO; KANSAS; N. MEXICO; OKLAHOMA; TEXAS

625,000 SQUARE MILES

400 MILLION ACRES]

[Narrator] The Grasslands: the treeless, windswept continent of grass ...

stretching from the broad Texas Panhandle, up through the mountain reaches of Montana, to the Canadian border.

A country of high winds and sun, high winds and sun.

Without rivers; without streams; with little rain.

[Music] [Crescendos]

[Narrator] First came the cattle ...

an unfenced range 1,000 miles long, an uncharted ocean of grass ...

the Southern range for winter grazing, and the mountain plateaus for summer.

It was a cattleman's paradise.

Up from the Rio Grande, in from the rolling prairies ...

down clear from the Eastern highlands ...

the cattle roamed into the old Buffalo range. Fortunes in beef. For a decade, the world discovered the grasslands. and poured capital into the Plains. The railroads brought markets to the edge of the Plains.

Land syndicates sprang up overnight, and the cattle rolled into the west.

The railroad brought the world into the Plains. New population, new needs crowded the last frontier.

Once again, the plowman followed the herder ...

and the pioneer came to the Plains.

[Trumpets]

[Narrator] Make way for the plowman!

The first fence.

Progress came to the Plains.

High winds and sun, high winds and sun. A country without rivers, and with little rain. Settler: plow at your peril!

200 miles from water!

200 miles from town!

But the land is new!

Many were disappointed.

The rains failed, and the sun baked the light soil.

Many left.

They fought the loneliness ...

and the hard years.

The rains failed them.

Many were disappointed.

[Farmer] [Angrily kicks stick across the ground]

[Narrator] But the great day was coming!

A day of new causes! New profits!

New hopes!

[EXPLOSION]

[TRUMPET][HERALD DISPATCH: ENGLAND DECLARES WAR ON GERMANY. BELGIUM INVADED. FRENCH WIN AT SEA.][WAR NEWS TUMBLES SECURITIES; STOCK EXCHANGE CLOSED; WHEAT PRICES SOAR.]

[WAR DRUMS]

[FARMERS DRIVE THEIR TRACTORS]

[EXPLOSION][WILSON PROCLAIMS WAR. SPY RING ARRESTED. GERMAN SHIPS SEIZED.][WAR SENDS WHEAT SOARING; GRAIN UP 13 POINTS; PIT IN PANDEMONIUM.]

[FARMERS DRIVE THEIR TRACTORS]

[CANNON EXPLODES]

[Narrator] Wheat will win the war! Plant wheat!

Plant the cattle feed!

[CANNON] [EXPLODES]

[Narrator] Plant wheat! Wheat for the boys over there!

Wheat for the allies! Wheat for the British! Wheat for the Americans!

Wheat for the French!

Wheat at any price!

Wheat will win the war!

[SHOOTING]

[FARMERS DRIVE THEIR TRACTORS]

[EXPLOSIONS]

[FARMERS DRIVE THEIR TRACTORS]

[WAR DRUMS]

[PEOPLE SHOUTING & CHEERING]

[FARMERS DRIVE THEIR TRACTORS]

[JAZZ MUSIC]

[Narrator] When we reaped the golden harvest, when we really plowed the Plains ....

[inaudible]. We had the manpower. We invented new machinery.

The world was our market.[SERVICE MEN!

FREE LAND!

GOVERNMENT HOMESTEADS IN THE PLAINS!!

OWN YOUR OWN FARM!!

APPLY

GENERAL LAND OFFICE

WRITE FOR PARTICULARS][RANGE LAND AT ROCK BOTTOM PRICES!

NEW SOD -- FINEST WHEAT LAND IN WEST!

A SECTION IN THE PLAINS -- YOURS FOR A DOWN PAYMENT!!

WESTERN CATTLE SYNDICATE][30,000 FARMS FOR SALE!!

3,000,000 ACRES OF PRIME LAND!!

A FEW DOLLARS NOW MEANS A FARM FOR YOUR OLD AGE!

GREAT PLAINS LAND COMPANY]

[Narrator] By 1933, the old grasslands had become the new wheat-lands.

100 million acres ...

200 million acres.

More wheat![YOU OWN IT -- WE FARM IT!

OWN A FARM AWAY FROM HOME!!

INVEST IN THE FASTEST-GROWING COUNTY IN THE WEST!

Come to Jonesville and See For Yourself

GENERAL FARM BROKERS, INC.][FORTUNES IN WHEAT FARMS!

ONE CROP RE-PAYS PURCHASE PRICE!!

EXAMINE OUR RECORDS AND SEE FOR YOURSELF!!

UNITED FARM CO., INC.][BARGAINS IN TOWN LOTS!!

THE HEART OF THE WHEAT LANDS!!

PRICES TRIPLED IN SIX MONTHS!!

ROUND-TRIP INSPECTION TRIP AT OUR EXPENSE --

WRITE NOW WHILE THESE BARGAINS ARE STILL AVAILABLE.

GREAT PLAINS REALTY COMPANY]

[FARMERS DRIVE THEIR TRACTORS AT NIGHT]

[GRAIN FLOWING]

[STOCK MARKET GOING UP]

[GRAIN FLOWING]

[JAZZ MUSIC PLAYS WILDLY]

[STOCK MARKET CRASHES]

[SKULL AND BONES]

[IDLE MACHINERY]

[SUN-BAKED EARTH]

[Narrator] A country without rivers, without streams, with little rain.

Once again the rains held off, and the sun baked the earth.

[DOG BREATHES HEAVILY]

[Narrator] This time, no grass held moisture against the winds and the sun.

This time, millions of acres of plowed land lay open to the sun.

[LITTLE DUST DEVIL]

[HERALD]

[WIND BLOWING]

[CHILDREN RUN FOR COVER]

[WIND BLOWING]

[MAN RUNS FOR COVER]

[WIND BLOWING]

[ORGAN MUSIC]

[DAY AS DARK AS NIGHT]

[Narrator] Baked out, blown out, and broke!

[Farmer] [Shoveling dust away from house]

[Narrator] Year in, year out ...

uncomplaining, they fought the worst drought in history.

Their stock choked to death on the barren land.

Their homes were nightmares of swirling dust night and day.

Many went to [inaudible]. But many stayed ...

until stock, machinery, homes ...

credit, food ...

and even hope were gone.

On to the west! Once again they headed for the setting sun!

Once again they headed west.

Last year, in every summer month, 50,000 people left the Great Plains ...

and hit the highways for the Pacific coast:

the last border.

Blown out, baked out, and broke.

Nothing to stay for ...

nothing to hope for.

Homeless, penniless, and bewildered ...

they joined the great army of the highway. No place to go, and no place to stop.

[Farmer] [Shakes dirt off his clothes]

[Narrator] Nothing to eat, nothing to do ...

their homes on four wheels ...

their work a desperate gamble for a day's labor in the fields along the highway ...

for the price of a sack of beans, or a tank of gas.

All they ask is a chance to start over, and a chance for their children to eat, to have medical care, to have homes again.

50,000 a month.

The sun and winds wrote the most tragic chapter in American agriculture.

THE END

[Narrator] The film placed much of the blame of the Dust Bowl on the arrival of the tractor to the Southern Plains, and described how sturdy farmers who had once slowly turned the soil behind a team of mules, suddenly became a mechanized force arrayed against nature itself.

[Timothy Egan, Writer] The reaction inside the Dust Bowl itself was largely not good. They didn't like seeing their land or themselves as characters on the bad end of a drama.

DROUGHT VICTIMS HIT DUSTY TRAIL FOR CITY RELIEF

[Pauline Durrett Robertson, Potter County, TX] Sometimes at the movies, the newsreel showed the Dust Bowl, and that infuriated the local Boosters, because they said, "That's bad publicity. We don't need that bad publicity." The rest of us besides the Boosters thought, "Well, they got that right, and they're really telling it, what's happening to us -- they're really telling it right.

[Narrator] In the summer of 1936, President Roosevelt took a 4,000-miles whistle-stop tour across the midwest and Northern Plains to see for himself the extent of the Nation's agricultural crisis.

[Franklin Roosevelt] My friends, I have been on a journey of husbandry. I talked with families who had lost their wheat crop, lost their corn crop, lost their livestock, lost the water in their well, and come through to the end of the summer without one dollar of cash resources, facing a winter without feed or food, facing a planting season ...

[Narrator] At the same time, Hugh Bennett, the head of the Soil Conservation Service, was on his own fact-finding tour with a committee of experts expected to make a report to FDR on the future of the Great Plains. Bennett's first stop was Dalhart, where Howard Finnell was making headway with the farmers he was trying to convert. Earlier in the year, Finnell had petitioned Secretary of Agriculture Henry Wallace for $2 million in emergency funds to offer incentives of twenty cents an acre for those who would try his method of contour plowing on their own land. Nearly 40,000 farmers had signed up and gone to work on 5.5 million acres.

[Donald Worster, Historian] The only program that was out there that was effective was this one, and Finnell was the point man to try to make it work among these farmers who had still not admitted that it was their fault, farmers who basically said, "This is all nature's doing. Leave us alone. The rains will come back, and we will be back in business."

[Narrator] Bennett and his Committee moved on with their tour, planning to meet up with the President in North Dakota and give him their findings. The final report estimated that 80% of the Great Plains was in some stage of erosion and pointed to what Bennett called "The Basic Cause" of the problem -- an attempt to impose upon the region a system of agriculture to which the Plains are not adapted." But, it concluded, the Nation "cannot afford to let the farmer fail." His boss was not about to let that happen.

[Franklin Roosevelt] Back East, there have been all kinds of reports that out in the drought area there was despondency, a lack of hope for the future, and a general atmosphere of gloom. But I had a hunch -- and it was the right one -- when I got out here, I'd find that you people had your chins out ...

[Crowd] [Applause]

[Franklin Roosevelt] ... that you are not looking forward to the day when this country would be depopulated, but that you and your children expect to remain here.

[Crowd] [Applause]

[Virginia Frantz, Beaver County, OK] To us, he was a savior. He just ... he gave us hope where we had none. I can remember my dad saying that he normally didn't vote Democrat, but he thought he would that time, and I think he became a staunch Democrat after that.

[Franklin Roosevelt] No cracked earth, no blistering sun, no burning wind are a permanent match for the indomitable American farmers and stockmen, and their wives and children, who have carried on through desperate days.

[Timothy Egan, Writer] Here's a land that God himself seems to have given up on ...

[Franklin Roosevelt] I shall never forget the fields of wheat ...

[Timothy Egan, Writer] ... and the fact that the President still gave it his attention -- so that was a very big deal at a time when they felt so abandoned, and you can't understate the importance of just giving it some attention.

[Franklin Roosevelt] It was their fathers' task to make homes, it is their task to keep these homes, and it is our task to help them win their fight.

IT'S THE AMERICAN WAY: FREEDOM OF RELIGION-SPEECH; OPPORTUNITY; REPRESENTATIVE DEMOCRACY; PRIVATE ENTERPRISE.

-- NATIONAL ASSOCIATION OF MANUFACTURERS.

[Man] We're continuing with Mr. Woody Guthrie's Dust Bowl songs from Texas, Oklahoma, and California.

[Woody Guthrie] As I rambled around over the country and kept looking at all these people, seeing how they lived outside like coyotes, around in the trees and timber and under the bridges and along all the railroad tracks and in their little shack houses that they built out of cardboard and toe sacks and old corrugated iron that they got out of the dumps -- that just struck me to write this song.

[Woody Guthrie] [Singing]

I ain't got no home, I'm just a-roamin' round

[Narrator] During the ten years of the Great Depression, California's population would grow more than 20%. Half of the newcomers came from cities, not farms. One in six were professionals or white-collar workers. Of the 315,000 who arrived from Oklahoma, Texas, and neighboring states, only 16,000 were from the Dust Bowl itself. But regardless of where they actually came from, regardless of their skills and their education and their individual reasons for seeking a new life in a new place, to most Californians -- and to the Nation at large -- they were all the same, and they all had the same name.

[Louise Forester Briggs, Daughter, Texas County, OK] "Okies." And we were made fun of, and, "You talk funny," and, you know, all of that. Or, "Talk some more. You talk funny." and you hated that because it set you apart.

[Donald Worster, Historian] There was a sign in a movie theater in the Central Valley of California which basically said "Niggers and Okies Upstairs." That is, you can't sit down here with real people.

Timothy Egan, Writer] They were horribly mistreated. In some cases, they were treated the way Blacks were treated in the South. There were signs similar to the signs they had in Dalhart, Texas, that said, "Black man, don't let the sun go down on you here." Similarly, there were signs all throughout the Central Valley saying, "Okie, go back. We don't want you."

[Narrator] About a third of all the recent arrivals, many of them former sharecroppers from the cotton belt, ended up in California's agricultural valleys, where farmers had always relied on migrant labor to pick their cotton, vegetables, and fruits. They settled in developments called "Little Oklahomas" and "Okievilles" or moved with the harvests, sometimes traveling 700 to 1,000 miles in the season, staying in squalid roadside camps called "jungles" or simply putting up a tent along the road or in an unused field. And they found themselves at the mercy of the contractors, who conspired with the growers to drive down the field workers' wages.

[Sanora Babb] They have the simple and sturdy values often bemoaned as lost. They are proud, strong people, patient, uncomplaining, intelligent. They want first of all to work, to have a home for their families, to educate their children. These simple rights are part of the heritage of Americans. It is difficult for them to understand that none of them remain. Their whole lives are concentrated now on one instinctive problem -- that of keeping alive.

[Narrator] Sanora Babb, a former reporter who had grown up in the area around No Man's Land, had found a new job with the Farm Security Administration. With her boss, Tom Collins, she went up and down the Central Valley, informing the newly arrived migrants about programs to provide them with food and medical assistance for their families, education for their children, and better living conditions.

[Sanora Babb] Only a few days ago, we met a young man walking along the road to town in search of immediate work and help. His wife had had a baby three days before in an abandoned milk house separated from any camp, where they had taken refuge during the recent storms. He was desperate. Since the birth, his wife, their other children, and he himself had not eaten for three days. If he did not get something for them at once, she and the baby would die.

[Narrator] When the refugees learned Sanora had grown up on the Southern Plains, it helped establish a trust and respect that extended both ways.

The government had also asked the photographer Dorothea Lange to come back to California to document the deplorable conditions among the migrants. Tom Collins and the FSA used her photos to push for creation of a handful of government camps with better shelter and sanitation for the steady stream of refugees who were arriving every day. Collins insisted that the camps be self-governed, with elected committees responsible for everything from sewing clubs and libraries to childcare and cleanliness. But only a lucky few were able to find space there. And while the growers depended on the migrants for cheap labor, the locals, who were themselves suffering from the Depression, didn't appreciate anything that encouraged the newcomers to stay. Nor did the growers once the harvest was over.

[Woody Guthrie] [Singing]

It takes a worried man

To sing a worried song

Takes a worried man

To sing a worried song

I'm worried now ...

[Narrator] Like many of the new arrivals, Woody Guthrie had settled in one of California's cities -- Los Angeles, where he worked washing dishes and singing in bars before finally landing his own show on radio station KFVD. Each day, he performed his own songs, as well as older folk tunes he had learned in Oklahoma and Texas, which reminded many listeners in his growing audience of the homes they had left.

[Woody Guthrie] [Singing]

I asked that judge

[Narrator] But though he was becoming a well-known radio personality, he, too, felt the sting of bigotry aimed at anyone considered an "Okie." He began spending time traveling and performing for free in the Central Valley, where the treatment of the farm workers politicized him, and his music, for the rest of his life.

WOODY & HIS GUITAR, SINGING HIS OWN SONGS, SONGS OF THE COMMON PEOPLE DEDICATED TO SKI-ROAD & DUST BOWL REFUGEES.

He sang at picket lines of workers holding out for higher wages, and started a newspaper column, "Woody Sez," in the left-leaning "People's World." "I ain't a Communist necessarily," he said, "but I've been in the red all my life."

[Woody Guthrie] [Singing]

Lots of folks back East, they say

Is leavin' home every day

Beatin' a hot old dusty way

To the California line

[Narrator] Guthrie was offended that the State legislature nearly passed a law closing the State's borders to people it called "Paupers and persons likely to become public charges."

[Woody Guthrie] [Singing]

Now, the police at the Port of Entry say

You're Number 14,000 for today

[Narrator] Then, without any legal authority, the Los Angeles Police Chief dispatched 125 of his officers to the main entry points from Arizona, Nevada, and Oregon. For six weeks, they intimidated anyone they considered "vagrants," including Clarence and Irene Beck's father Sam, from Wheeless, Oklahoma.

[Clarence Beck, Cimarron County, OK] My father was a Dust Bowl okie. He got put in jail when he crossed into California because he didn't have 50 bucks. When he was arrested, he was arrested as a vagrant and would have gone to jail except that one of his ex-neighbors in Oklahoma knew he was coming and was prepared for this and met him, arranged that he could stay with them so he no longer was a vagrant.

[Narrator] For a while, Beck was allowed to stay at a chicken farm, where he worked in exchange for eggs to eat. But he finally landed a job with the Los Angeles Highway Department and started a new life for himself and his daughter.

[Irene Beck Hauer, Cimarron County, OK] It's a fresh start. I guess that's the words to use -- a fresh start, which it was. It really was. So thank God of that. I was blessed that way.

[Narrator] Sam Beck died of a heart attack in 1947, at age 54, spreading blacktop on a California highway.

[Clarence Beck, Cimarron County, OK] He had a tough life. A very tough life. He and his life was the reason that I said, "God, what do I have to do to have money and not be a farmer, and I'll do it. And I don't care whether it's being a pimp. I don't care whether it's stealing. Whatever it takes, I'm not gonna farm, and I'm not going to be broke." And that's been my driving force. It has been. And I'm not a farmer, and I'm not broke. And I'm not a pimp, either, thank God.

FARM LABOR INFORMATION HERE! DEPARTMENT OF EMPLOYMENT. CALIFORNIA STATE EMPLOYMENT SERVICE.

[Woody Guthrie] [Singing]

I'm a Dust Bowl refugee

[Narrator] Calvin Crabill's father, John, had rescued his wife and family from the dust of Eastern Colorado, but the hard times followed him to Southern California. He moved from one temporary job to another -- a Colorado cowboy, far from the Plains he loved.

[Calvin Crabill, Prowers County, CO] My father was called an Okie. He was a gentle, quiet man, so I think he could take it pretty well. It made me with a chip on my shoulder that I probably carry to this day, that I was very aware that I thought I was the poorest kid in high school. We rented a little house on the alley in Burbank, and the house in front, the people had more money, and they were very aware that we were the poor people on the block. In those days, you could get something to put on your license plate that would be some kind of a slogan. Well, it said "Peaceful Valley," and so my father liked that place, so he put it on his license plate. And the people at his job crossed out the "V" and wrote "Peaceful Alley" because they knew he lived on an alley. So if you're down, they push you down, fella, they push you down, and that's what happened to him, over and over and over, over and over.

[Sanora Babb] How brave they all are. I have not heard one complaint. They all want work and hate to have help.

[Narrator] As she moved from camp to camp, Sanora Babb kept a nightly journal, which she planned to turn into a novel, about the people she had met and what they had gone through. She also wrote detailed reports for her boss Tom Collins, who was regularly sharing her notes with a writer working on a muck-raking article for the San Francisco News named John Steinbeck.

[Sanora Babb] When Steinbeck first came, he had to stop seeing them before the day was out. Tom Collins said he said, "By God, I can't stand anymore. I'm going away and blow the lid off this place."

[Narrator] Sanora Babb would eventually send some chapters of her novel to Bennett Cerf, a prominent editor of Random House in New York City, who was so impressed he asked her to come East to talk about it. But by the time she arrived, in the winter of 1939, Steinbeck had come out with his own Pulitzer prize-winning novel, The Grapes of Wrath, which chronicled the tribulations of the Joad family, tenant farmers who had migrated to California, from the cotton fields of Eastern Oklahoma -- not the Dust Bowl. The book was such a hit that the market couldn't support a second novel on the same subject, and her editor advised Sanora to put her manuscript aside. It was finally published in 2004, a year before her death.

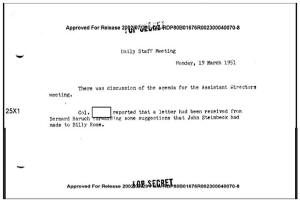

Redacted CIA memo mentioning John Steinbeck shown

My discovery of John Steinbeck’s connection to the CIA could be described as payback for a youthful indiscretion—my own, not the author’s. While reading The Grapes of Wrath in high school, I skipped the “turtle” and other chapters that seemed to me superfluous to the plot line of the Joads’ journey west. The punishment for my teenage sin of omission came years later, when it first occurred to me that John Steinbeck was a CIA spy. The insane-sounding proposition grew from incongruities in Steinbeck’s life that—unlike Tom Joads’ turtle—I found I couldn’t ignore.

Steinbeck: Citizen Spy book cover shown with subtitle: The Untold Story of John Steinbeck and the CIA

FOIA to the CIA: What Do You Have on John Steinbeck?

Why was Steinbeck never called before the House Select Committee on Un-American Activities, despite his alleged ties to Communist organizations? Why did the CIA admit to the Church Committee in 1975 that Steinbeck had been a subject of the illegal CIA mail-opening program known as HTLINGUAL? Did Steinbeck’s connections to known CIA front organizations, such as the Congress of Cultural Freedom and the Ford Foundation, amount to more than mere coincidence? Did the synchronicity continue when Steinbeck did freelance writing for the Louisville Courier-Journal and New York Herald Tribune? Both newspapers were linked to MOCKINGBIRD, another CIA operation, in Carl Bernstein’s 1977 Rolling Stone article “The CIA and the Media.” Why did the CIA redact portions of Steinbeck’s FBI files before they were released under the 1966 Freedom of Information Act (FOIA), the law that permits full or partial disclosure by government agencies of previously classified documents on request?

There was only one source—the CIA itself—that could definitively answer my questions and confirm or disprove my developing conclusions. I submitted my FOIA request to the CIA in January 2012. With characteristic bureaucratic speed, the CIA responded after eight months, in August 2012, sending me copies of two letters written in 1952. In the first, penned on personal stationery in his own handwriting, Steinbeck offers to work for the CIA. In the second, then-CIA Director Walter Bedell Smith accepts Steinbeck’s offer. The text of these letters and others can be found in my book, Steinbeck: Citizen Spy, at my website or in the FOIA Electronic Reading Room.

The CIA Director Accepts the Author’s Offer of Help

Jan 28, 1952

Dear General Smith:

Toward the end of February I am going to the Mediterranean area and afterwards to all of the countries of Europe not out of bounds. I am commissioned by Collier’s Magazine to do a series of articles—subjects and areas to be chosen by myself. I shall move slowly going only where interest draws. The trip will take six to eight months.

If during this period I can be of any service whatever to yourself or to the Agency you direct, I shall be only too glad.

I saw Herbert Bayard Swope recently and he told me that your health had improved. I hope this is so.

Also I wear the “Lou for 52” button concealed under the lapel as that shy candidate suggests.

Again—I shall be pleased to be of service. The pace and method of my junket together with my intention of talking with great numbers of people of all classes may offer peculiar advantages.

Yours sincerely,

John Steinbeck

***

ER 2-5603

6 February 1952

Mr. John Steinbeck

206 East 72nd Street

New York 21, New York

Dear Mr. Steinbeck:

I greatly appreciate the offer of assistance made in your note of January 28th.

You can, indeed, be of help to us by keeping your eyes and ears open on any political developments in the areas through which you travel, and, in addition, on any other matters which seem to you of significance, particularly those which might be overlooked in routine reports.

It would be helpful, too, if you could come down to Washington for a talk with us before you leave. We might then discuss any special matters on which you may feel that you can assist us.

Since I am certain that you will have some very interesting things to say, I trust, also, that you will be able to reserve some time for us on your return.

Sincerely,

Walter B. Smith

Director

O/DCI:REL:leb

Rewritten: LEBecker:mlk

Distribution:|

Orig – Addressee

2 – DCI (Reading Official) [“w/Basic” has been handwritten beside this line and scratched out]

1 – DD/P [a check mark and w/Basic handwritten in]

1 – Admin [This has been scratched out] handwritten is “w/Basic”

***

Did Steinbeck’s CIA Connection Start in Russia?

Reread A Russian Journal with the possibility that Steinbeck was working for the CIA prior to 1952 in mind. When Steinbeck traveled to the USSR with Robert Capa in 1947—the second of three trips the author made to the Communist state during his lifetime—Walter Bedell Smith happened to be the U.S. Ambassador to Russia. Steinbeck notes in his account of his and Capa’s Russian journey that they dined with Smith during their stay.

This experience helps explain the personal tone of familiarity expressed in Steinbeck’s 1952 letter to Smith offering to help the CIA. It also suggests the possibility that Steinbeck used his access while in the USSR to gather intelligence for the U.S. government from the Russian interior. While visiting a factory in Stalingrad, Steinbeck observes that the Russians are still melting down hulls from German tanks to make tractors fully two years after the end of World War II, lamenting his frustration at not being able to get current production figures for the facility. Such information would have been particularly important to the U.S. government in 1947, as the Cold War became hotter and American travel behind the Iron Curtain more difficult.

The 1952 exchange between the author of The Grapes of Wrath and the Director of the CIA provides a new set of parameters for understanding John Steinbeck’s life. In my book I carefully examine each of the letters resulting from my FOIA request to the CIA, the writer’s heavily CIA-redacted FBI files, Thomas Steinbeck’s thoughts on the matter, and likely avenues through which the elder Steinbeck could have served his government covertly both before and after 1952. Viewing the author’s life in terms of possible links to the CIA opens vistas for better comprehending certain works, such as The Short Reign of Pippin IV, that his literary agent, editor, and others discouraged him from writing.

The Short Reign of Pippin IV: A Fabrication is a novel by John Steinbeck published in 1957; his only political satire, the book pokes fun at French politics.

Plot summary

Pippin IV explores the life of Pippin Héristal, an amateur astronomer suddenly proclaimed the king of France. Unknowingly appointed for the sole reason of giving the Communists a monarchy to revolt against, Pippin is chosen because he was rumored to descend from the famous king Charlemagne. Unhappy with his lack of privacy, alteration of family life, uncomfortable housings at the Palace of Versailles and mostly, his lack of a telescope, the protagonist spends a portion of the novel dressing up as a commoner, often riding a motorscooter, to avoid the constrained life of a king. Pippin eventually receives his wish of dethronement after the people of France enact the rebellion Pippin's kingship was destined to receive.

-- The Short Reign of Pippin IV, by Wikipedia

In recommending my book to a Steinbeck blogger, a noted Steinbeck scholar described the possible CIA-Steinbeck connection detailed in Steinbeck: Citizen Spy as “a potential game-changer.”

Time will tell.

COMMENTS

bill steigerwald says:

October 4, 2013 at 12:51 pm

Great work. Steinbeck’s connection with the CIA makes a lot of sense. He was, despite his leftist reputation, very anti-communist and patriotic. I’m sure he wasn’t shooting microfilm of those great old Soviet tractor factories or doing any recruiting, but when he went into the USSR and behind the Iron Curtain he didn’t play along with his host’s propaganda machine. He didn’t trash America’s foreign policy from Moscow like some other celebrity dupes/useful idiots. And he made a point to seek out and encourage dissident writers in Eastern Europe. Then there was Steinbeck’s hawkish support of the war in Vietnam and his sleepovers at the LBJ White House, which make his lefty-liberal supporters squirm and search for proof that he turned into a dove on his deathbed. Steinbeck was always a New Deal Stevenson Democrat/Cold War liberal and never as left-wing as his progressive friends wished and conservative enemies charged. But apparently he didn’t just suck up to political power, he offered to do freelance spy work for it.

***

William Ray says:

October 4, 2013 at 2:35 pm

Another comparison could be made as context for your point: Henry “Scoop” Jackson, the left social/right defense U.S. Senator from the State of Washington. Thank you for reminding readers that both foreign-interventionist Presidents between Teddy Roosevelt and LBJ were Democrats, Woodrow Wilson and FDR, and that the isolationists who opposed American entry into European wars were Republicans, such as Senator Henry Cabot Lodge from Massachusetts. History can be quite as surprising as the future when actually studied.

***

Martin Maloney says:

October 17, 2013 at 5:30 am

I was active in the movement against the war in Vietnam. John Steinbeck appeared before a congressional committee and testified in favor of that war. As I recall, he had a son in military service in Vietnam.

It seemed incongruous to me at the time that someone who had written “The Grapes of Wrath” could support the Vietnam war.

After reading this article, it makes perfect sense.

***

William Ray says:

October 17, 2013 at 1:53 pm

Thank you, Martin. Look for my blog post about Brian Kennard’s book on Steinbeck and the CIA later today. You’re right. Both of John Steinbeck’s sons served in Vietnam. Kennard treats this phase of the author’s public politics candidly and compellingly in the book, which I highly recommend.

-- Did John Steinbeck Work as A Citizen Spy for the CIA?, by Brian Kannard

Indeed, over the years, the CIA had been engaged in the business of trying to suppress books rather than encouraging them. In 1964, for example, John A. Bross, then the CIA's comptroller, got the bound galley proofs of David Wise and Thomas B. Ross's book The Invisible Government. The book was an expose of the CIA, FBI, and other agencies that had engaged in illegal activities. Bross obtained the galleys through a friend of a family member who was then working for Random House. With the authorization of John McCone, then DCI, the CIA asked Bennett Cerf, president of Random House, if the agency could buy up the first printing.

Cerf responded that he would be delighted to sell the first printing to the CIA, but then immediately added that he would then order another printing for the public, and another, and another," according to Wise's subsequent book, The American Police State. The agency dropped the idea.

While the CIA would have liked to have brought legal action against the authors, they were journalists, not former employees. The CIA has gone to court only to enforce contracts signed by CIA employees when they enter and leave employment.

-- Inside the CIA, by Ronald Kessler

According to Wise, CIA officials considered buying up all the copies, but abandoned the idea when Random House chief Bennett Cerf pointed out that he could print a second edition. Instead, McCone formed a "special group" inside the Agency to sabotage the book. Its number 1 weapon: bad reviews written by CIA agents under code names and passed to cooperative journalists and publishers; among the fake reviewers was E. Howard Hunt, later of Watergate burglary fame.

Following that, in 1965, the New York Times decided to launch its own investigation of the CIA, triggered by a slip of the tongue by Congressman Wright Patman (D-Tex.) the previous year. As chair of the House Banking Committee, Patman had convened hearings to explore whether foundations were being used as tax dodges. The congressman inadvertently identified the J.M. Kaplan Fund as a CIA conduit, and named eight (phony) foundations that passed funds through it. CIA officials rushed to Patman's office. The following day, Patman announced that the CIA had nothing to do with his hearings and declared the matter ended.

But the episode caused the Times' managing editor, Turner Catledge, to pay more attention to CIA activity. On September 2, 1965, Catledge noticed an odd story coming out of Singapore. Prime Minister Lee Kuan Yew publicly revealed that five years earlier the CIA had offered him a $3.3 million bribe for the release of two CIA agents who had been arrested. Yew had demanded $35 million, but ended up taking nothing in return for their release. Details of the story were truly bizarre, but the prime minister had produced as evidence a letter of apology from Secretary of State Dean Rusk. Times journalist Harrison Salisbury remembers Catledge thundering, "For God's sake let's find out what they are doing. They are endangering all of us." The Times Washington Bureau chief Tom Wicker, drafted a survey to send to the newspaper's worldwide network of journalists asking what they knew about the CIA. What were their experiences with the agency?

James Jesus Angleton, the CIA counterintelligence chief whose job was to look for Soviet moles, had a copy of the survey before the ink was dry. The legendary Angleton had grown steadily paranoid after decades of professionally suspecting everyone of pro-Moscow sympathies. According to Salisbury, Angleton regarded the journalistic survey as a KGB instrument; the very phrasing of the questions "betrayed the hand of Soviet operatives." While Angleton's reaction might have seemed extreme, the response to the Times survey at CIA stations around the world was similar.

CIA media liaison Colonel Stanley Grogan sent a memo to McCone, "NEW YORK TIMES Threat to Safety of the Nation," in which he suggested using the CIA's "heaviest weapons," including White House pressure, to combat the Times. Salisbury, who saw the memo, described it as a scream from outer space. "Any questions, any attempt to probe what the CIA was doing, how it operated, what its intentions might be, was seen as hostile, dangerous and frightening, capable of destroying the agency."

In late April 1966, in the midst of the CIA furor over the two Ramparts articles, the Times published the fruits of its investigation in a series of five articles. While listing some of the CIA accomplishments, the articles depicted the Agency as without oversight; seemingly the government had no control over its increasingly questionable behavior. Richard Helms, then Raborn's deputy, moved quickly to contain the damage, successfully killing a planned book based on the articles. Most of all, Salisbury noted in his memoir, the CIA feared a permanent record, available and accessible to all. He and Wicker thought that the CIA response was hysterical in the extreme, but they could not persuade the higher-ups to publish the book.

-- Patriotic Betrayal: The Inside Story of the CIA's Secret Campaign to Enroll American Students in the Crusade Against Communism, by Karen M. Paget

[Sanora Babb] You, who live in any kind of comfort or convenience, do not know how these people can survive these things, do you? They will endure because there is no immediate escape from endurance. Some will die. The rest must live.