Collected and Edited by William Knight

Boston and London, Ginn and Company, Publishers, 1907

© 1907 by William Knight

NOTICE: THIS WORK MAY BE PROTECTED BY COPYRIGHT

YOU ARE REQUIRED TO READ THE COPYRIGHT NOTICE AT THIS LINK BEFORE YOU READ THE FOLLOWING WORK, THAT IS AVAILABLE SOLELY FOR PRIVATE STUDY, SCHOLARSHIP OR RESEARCH PURSUANT TO 17 U.S.C. SECTION 107 AND 108. IN THE EVENT THAT THE LIBRARY DETERMINES THAT UNLAWFUL COPYING OF THIS WORK HAS OCCURRED, THE LIBRARY HAS THE RIGHT TO BLOCK THE I.P. ADDRESS AT WHICH THE UNLAWFUL COPYING APPEARED TO HAVE OCCURRED. THANK YOU FOR RESPECTING THE RIGHTS OF COPYRIGHT OWNERS.

-- The History of the Fabian Society, by Edward R. Pease

-- Pantisocracy, by Wikipedia

-- Critias, by Plato

-- The Heroic Enthusiasts: An Ethical Poem by Giordano Bruno

-- Monism, by Wikipedia

-- The Story of Sigurd the Volsung, by William Morris, et al.

-- Triumph of the Will, directed by Leni Riefenstahl

-- On the Constitution of the Church and State, According to the Idea of Each; With Aids Toward a Right -- Judgment on the Late Catholic Bill, by Samuel Taylor Coleridge

-- The Prophets of Israel and Their Place in History to the Close of the Eighth Century, B.C., by W. Robertson Smith, LL.D.

Table of Contents:

• Preface

• 1. Introductory

• 2. The Man: a Sketch and an Estimate

• 3. Formation of the Fellowship of the New Life

• 4. The Occasion, Principles, Rules, Creed, and Organization of the New Fellowship as drawn up by Thomas Davidson

• 5. Development of the Society

• 6. Estimates of Davidson by Percival Chubb and Felix Adler

• 7. Letters to Havelock Ellis

• 8. Reminiscences by Havelock Ellis

• 9. The New York Branch of the New Fellowship

• 10. The Summer Schools of the Culture Sciences at Farmington and Glenmore

• 11. Recollections of Glenmore by Mary Foster

• 12. Charlotte Daley's Retrospects of Davidson's Teaching

• 13. Lectures to the Breadwinners

• 14. Letters from Davidson in Reference to his Work on Medievalism

• 15. Professor William James's Reminiscences and Estimate

• 16. Recollections by Wyndham R. Dunstan

• 17. The Moral Aspects of the Economic Question

• 18. Letters to Morris R. Cohen

• 19. Rousseau, and Education according to Nature

• 20. Intellectual Piety

• 21. Faith as a Faculty of the Human Mind

• APPENDIX

[H]e was, as wise men are, both gnostic and agnostic; gnostic as to the root ideas of the true, the beautiful, and the good; agnostic as to the terra incognita [Google translate: unknown land] which lies behind them, and the ultimate principle of things. In this he was essentially Hebraic and profoundly Christian. I think that he believed the real and the ideal to be one, and that they are known together in perpetual synthesis, — " the real apprehended through its ideality, and the ideal grasped in its reality," as I once put it to him.

***

I have said that he had no elaborated system to offer and to teach; but he had many resting-places in his forward journey. One of them, and perhaps the most important, was the philosophy of Rosmini, in which pantheistic monism is met by an individualism proclaiming the inherent and intrinsic value of every unit in the race. According to this teaching each one of us is an impenetrable unit, cut off from every other by the boundaries which limit, form, and determine his individuality. But each of the units resembles every other one: all have points of contact, and can disclose their individualities to others. Each is the heir of all the ages, not only by unconscious inheritance, but because the gains of the past, all ancestral possessions, can be entered into a fresh, reappropriated by culture, and lived over again in new experience; while that experience, after receiving its own enrichment from the past, is destined to give place to a larger and fuller one. Every individual yearns for new development and fresh environments, but what it is possible for each to realize is met by the discernment of what it is good for others to experience. The worth of particular states, however, cannot be known, a priori, in the abstract. It can only be known through the experiences themselves. Thus Davidson's philosophy was both individualistic and pluralistic. When experience is analyzed we find a unity within the plurality; and in that unity is found, and out of it may be deduced, a theism of which the evidence is clear and the outcome stable.

The psychological, metaphysical, and ethical teaching of Thomas Davidson is well known to those who heard him teach. It is with its results that I have chiefly to do in this volume; especially with the outcome of his ethical teaching. Very early in life he saw that "man's chief end" (as his Scottish catechism put it) was the attainment of knowledge, insight, and freedom, — the realization of what is true, and beautiful, and good; but he also saw that this had to be conjoined with the realization of an equally supreme good or "chief end" by others, that is to say, by the community. It was this double or twin conviction, more than anything else, that dominated his whole life. The chief good for each, and the summum bonum for all, were not theoretically antagonistic; and they did not practically conflict. But, how were they to be realized and harmonized? It was his prolonged pondering and revolving of this problem that led him to his "Fellowship of the New Life." The very name "fellowship," rather than "society" or "organization," meant a great deal. It carried its small band of devotees back to the Pythagorean, the Socratic or Platonic, and the Epicurean brotherhoods. Even the manual labor called for from each member was significant. But Davidson soon saw that he could not realize his ideal in England. It was Utopian to his British contemporaries. Hence he sought for it in the New World, "the unexhausted West."

As, however, his aim has been a good deal misunderstood, it is desirable again to state that the "New Fellowship," the realization of which he sought for, was based not upon uniformity of opinion or belief, not on mere camaraderie, or sympathy in pursuing ends which are not ideals; but on the realization of the highest possible life, the broadest and most varied culture, altruistic in every sense from first to last. To Thomas Davidson culture was not a selfish pursuit that could be followed out in solitude. It was only attainable in a community established and knit together by disinterested social bonds, the varied knowledge sought being obtained with a view to the elevation and betterment of society around. His aim was to present to the world a new example of "plain living and high thinking" by the courageous pursuit and advocacy of truth when freed from the trammels of convention, and by the realization of the beautiful in Art and of the good in Life. If a parallel to this may be found in earlier efforts, it is to be sought, not in the phalanstery [Merriam Webster: a Fourierist cooperative community; French phalanstere dwelling of a Fourierist community, from Latin phalang, phalanx + French stere (as in monastere monastery) schemes of the eighteenth-century economists, but in the pantisocracy of Samuel Taylor Coleridge and his friends, and their projected settlement on the banks of the Susquehanna. The "Fellowship of the New Life," however, was wider in its original programme, much fuller and richer in its ideals, although not more realizable in the world of the actual.

***

It was his intellectual and social ambition to find a set of men and women who could be bound together in the freemasonry of a common thirst for that knowledge which leads to useful work and fruitful life....As an intellectual missionary, his aim was to get at the truth of things, with a view to the regeneration of society. He wished the elimination of error to lead to, and insure, the eradication of evil from human life. His unique advocacy of the philosophy of Religion, his defence of dualism against the monistic system of Spinoza, his glorification of individualism — dualistic yet socialistic — were notable amongst other efforts of his countrymen....he has left the memory of a mediaevalist panoplied in the guise of a nineteenth-century crusader.

***

Except in the domestic circle there is to be no distinction between the sexes.... All authority in the society, except that which is constituted by the society itself, is null and void.

***

"He was a remarkable man, intellectually and emotionally; intense in his convictions and in his likes and dislikes, large-hearted and recklessly generous of time and strength to those who sought his help. He was especially attracted by promising young men, for whom he had a romantic feeling that was in the best sense Hellenic. There was scarcely a period of his life when he did not lavish upon some hopeful and needy youth the best of his intellectual powers and stores, often money from his none too copious supply, always an ebullient childlike affection and loyalty, an unselfish and delicate thoughtfulness.

Intellectually Mr. Davidson always bore the marks of his Scottish origin. He was modern in his equipment and in his outlook; but with this modernness was mingled a touch of the scholasticism and the sectarian fire, the parti pris, of a John Knox. He was almost fiercely affirmative of his own convictions; they were the bread of life to him. He boasted that he was sectarian; he always believed that his philosophy was the supreme way to salvation; and he was at all times an ardent, fearless, outspoken missionary in its behalf. What that philosophy was it would be difficult to formulate, for it underwent many changes. He remained a devout Aristotelian, and an arch-enemy of the Spenceriacs (as he called them) and Hegelians. He owed much to the mediaeval men, — Aquinas and Bonaventura and Dante; and among his more modern devotions were those to Giordano Bruno, Leibnitz, Goethe, and Tennyson....

But nothing was more admirably characteristic of the man than the labors which during the last two years of his life he carried on at the Educational Alliance on the lower East Side of New York. Here he had gathered about him, in peculiarly close bonds, a body of young Russian Hebrews, whom he endeavored to help to get culture in the broadest, manliest sense of the term. More important, we are led to believe, than any actual results in scholarship achieved was the powerful, transforming, personal influence exerted over these young boys and girls by a man who could show in such relationships a magnetic charm, a sympathy and tenderness of interest, a whole-souled devotion which will undoubtedly have left a deep mark upon many lives. The labor was a labor of love. The man's whole soul was in it.

***

[T]he want of a spiritual light, the childish prejudice against 'metaphysics,' the absence of whole-heartedness, the fear of ridicule. Kant and Comte have done their work, taken the sun out of life, and left men groping in darkness. A recent German book opens with the sentence, 'Kant must be forgotten,' and this I cordially echo. The present crude notions about metaphysics must be put away, and the fact clearly brought to light that without metaphysics even physics are meaningless, that that which appears also is, that beneath all seeming is that which seems. To me it is puerile to question this; but reactionary philosophies have brought many men to a different conclusion with what I cannot but consider a miserable result. You miss a positive basis in our little programme. The fact is there never can be any positive basis for anything but a metaphysical one, for the simple reason that all abiding reality is metaphysical; that is to say, lies behind the physical or sensuously phenomenal.

***

The good things ... To me they are the enjoyment of the eternal, and continual sacrifice of the temporal self to the eternal self. Morality means that, and nothing but that. But we must be careful not to fall into Buddhism and suppose that we are to sacrifice an eternal self to a monistic self in which all distinction is lost, and in which sacrifice of self would cease to be possible. Hinton continually falls into this grave error. The eternal is not the formless, and the unindividuated. It is the individuated, and eternally formed. You and I are eternal forms, whose inexhaustible taste with reference to each other is to penetrate each other through inexhaustible love and knowledge. 'God is love.' God is the loving, knowing interpretation of eternal forms. He is joy, life, light, 'letizia che trascende ogni dolzore.' We must never forget that. He is the ideality of which we are the reality. But if the reality should cease, so likewise would the ideality. He is the object to which we are subjects, infinite in multitude. As I have said often, He is the 'law of being,' and in that law we live and move and have our being.... When a man has realized his eternity, flesh and blood are only obstacles to him.

***

That this world is the only actual and eternal one is so plainly not true that I cannot imagine any serious man maintaining that it is. Either he is talking paradox intentionally, or else he does not know the meaning of the word he is using. Mr. Hinton plainly was in the latter predicament. . . . The truth is 'this world,' — the world of phenomena and change — is not actual at all, much less is it eternal. . . . We must distinguish the actual from the real, the eternal from the continuous. ... To say that 'everything of real spiritual value may be attained in this world' is to use words without meaning. The only thing of spiritual value is eternal self-possession, and to say that this can be attained in time is as untrue as anything can be. What is the use of an attainment that is lost the instant it is attained? For whom, or for what, is it attained? Are we mere rockets whose aim is to rise to a certain brilliant height, only to fall back instantly, like a stick into the dark? Those who say so are utterly and totally blind to the true life of the soul.

***

That the moral law is 'Act with reference to the eternal' is to me the deepest and most momentous of all truths. . . . We must withdraw into the eternal, and work from that into endless time. For eternity is by no means endless time. Eternity is that in which there is no succession possible: endless time is the form of infinite succession. I do not see how two things could be more different, or how any difference could be more clear.

***

His doctrine — at this time at all events — may be stated in a few words, as the absolute necessity of founding practical life on philosophical conceptions; of living a simple, strenuous, intellectual life, so far as possible communistically, and on a basis of natural religion. It was Rosminianism, one may say, carried a step further.

***

It so happened that William Morris was coming to read portions of his Sigurd at one of the meetings of a sort of ethical society, in which I was interested. Davidson admired Morris, and we asked him to preside at the meeting.

***

The Purposes of the Fellowship shall be the cultivation of character in the persons of its members, and the attainment of whatever follows from high character. The ideal of character shall be perfect purity or holiness, including perfect intelligence, perfect love and freedom — that freedom which springs from perfect obedience to the divine laws of the spirit. Truth and love alone shall have authority in the Fellowship, and in all cases the material and fleshly shall be subordinated to the spiritual.

***

The Fellowship of the New Life is essentially a religious society, that is, a society whose members seek to order their lives in accordance with the Supreme Will (by whatever name it may be called — God, Holiness, Intelligence, Love), in so far as that can in any way be ascertained. Its religion, however, in contradistinction to other religions, is purely one of attitude; attitude of the whole human being, mind, affections, will. It seeks, through the persons of its members, to be receptive toward all truth, whatever its mediate source, responsive with due love toward all worth, and active toward all good.

***

In endeavoring to know well, the members of the Fellowship, far from depending solely on individual reason or experience, seek light and aid from every quarter; from every age and people; from religion, science, and philosophy; from nature and art; from reason and faith. Knowing that their own mental and moral status, the very conceptions by which they interpret experience, and the thought by which they unite them into a known world, as well as the language by which they express all this, are not their own products, but are the outcome of a process of mental unfolding dating back far beyond the dawn of recorded history, and are to be understood only through a knowledge of this process, they can look only with pity upon those persons who, having no comprehensive acquaintance with the history of human conceptions, rashly undertake, with their crude notions, to pronounce upon the great problems of life and mind. They are, therefore, neither dogmatists, skeptics, nor agnostics, but reverent students of the world of nature and of mind, seeking to supplement their own experience and conclusions with the experience and conclusions of the serious men and women of all time. Inasmuch as they are not called upon to accept any special beliefs, but only to be honest and circumspect with themselves in accepting any belief whatever, it follows that no honest belief or unbelief need prevent any one from being a member of the Fellowship. The man who finds cogent reasons for believing in the doctrines of transubstantiation and the immaculate conception, and the man who finds it impossible to attach any definite meaning to the word God, are equally in their place in the Fellowship, provided they are equally sincere. But sincerity is not possible apart from a living desire for ever deeper insight, and a sympathy with those who sincerely hold opinions different from our own.

***

Such wrong emphasis we see in all those philanthropic movements whose chief aim is men's physical comfort and the indiscriminate removal of that powerful natural corrective, suffering. With such movements the Fellowship, realizing how beneficial suffering may be, has no sympathy. Better to suffer and be strong, than to be comfortable and weak.

***

The way to begin the New Life, I believe, is to try to forget oneself, one's sorrows, one's annoyances; to count oneself happy, if he can have the approval of a good conscience and the sense of having furthered the good. The New Life, as I conceive it, is a new attitude of the intelligence, the feelings, the will — a desire to lay aside all prejudice and to know the absolute truth, a wide, sweet sympathy, recoiling at no sin, no suffering, no hardness of heart, but only at selfishness and meanness and lying, a firm resolution to do the best, as far as that is known, in the spirit of love. Such a life, I know, is worth living. It is a life in which all wounds soon heal, and all scars are but brands of victory — legal tender for future blessedness.

***

And what if it be true that all great attainment calls for suffering, that such is the law of our being? Shall we slink back and tremble, and drug ourselves, like craven cowards? Never! The pure metal rings when it is struck, and the true soul finds itself and its own nobility often only in the throbs of pain and utter self-sacrifice. One true act of will makes us feel our immortality: alas! that we so seldom perform an act of will. In the face of an act of real will, heredity counts as nothing. What makes heredity tell is our own cowardice and sluggishness in not forcing children to conquer it, and also in not conquering it in ourselves. Heredity, like corruption, acts only when the soul is gone. It is utterly debasing to be bullied by heredity. The belief in its power "shuts the eyes and folds the hands," and delivers the soul in chains to the demon of unreality. The reason why people doubt about the freedom of the will is because they never exercise it, but are always following some feeling or instinct, some private taste or affection. How should such persons know that the will is free? Our time is dying of sentimentality — some of it refined enough, to be sure, but sentimentality — which destroys the will.

We are on our way to all that heart ever wished or head conceived. But the greater gods have no sympathy with anything but heroism. When we will not be heroic they sternly fling us back to suffer, saying to us: Learn to will! The kiss of the Valkyre, which opens the gates of Valhalla, is sealed only upon lips made holy by heroism even unto death.

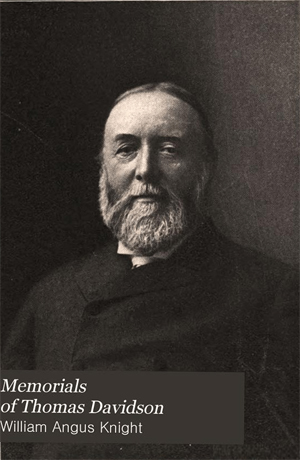

-- Memorials of Thomas Davidson, The Wandering Scholar, Collected and Edited by William Knight