§ 1. Rent the Effect of a Natural Monopoly.

The requisites of production being labor, capital, and natural agents, the only person, besides the laborer and the capitalist, whose consent is necessary to production, and who can claim a share of the produce as the price of that consent, is the person who, by the arrangements of society, possesses exclusive power over some natural agent. The land is the principal of the natural agents which are capable of being appropriated, and the consideration paid for its use is called rent. Landed proprietors are the only class, of any numbers or importance, who have a claim to a share in the distribution of the produce, through their ownership of something which neither they nor any one else have produced. If there be any other cases of a similar nature, they will be easily understood, when the nature and laws of rent are comprehended.

It is at once evident that rent is the effect of a monopoly. The reason why land-owners are able to require rent for their land is, that it is a commodity which many want, and which no one can obtain but from them. If all the land of the country belonged to one person, he could fix the rent at his pleasure. This case, however, is nowhere known to exist; and the only remaining supposition is that of free competition; the land-owners being supposed to be, as in fact they are, too numerous to combine.

The ratio of the land to the cultivators shows the limited quantity of land. It is very desirable to keep the connection [pg 233]of one part of the subject with another wherever possible. “Agricultural rent, as it actually exists,” says Mr. Cairnes,180 truly, “is not a consequence of the monopoly of the soil, but of its diminishing productiveness.” The doctrine of rent depends upon the law of diminishing returns; and it is only by the pressure of population upon land that the lessened productiveness of land, whether because of poorer qualities or poorer situations, is made apparent. Or, to take things in their natural sequence, an increase of population necessitates more food; and this implies a resort to more expensive methods, or poorer soils, so soon as land is pushed to the extent that it will not yield an increased crop for the same application of labor and capital as formerly. Different qualities of land, then, being in cultivation at the same time, the better qualities must, of course, yield a greater return than the poorer, and the conditions then exist under which land pays rent. Those, therefore, who admit the law of diminishing returns are inevitably led to the doctrine of rent.

§ 2. No Land can pay Rent except Land of such Quality or Situation as exists in less Quantity than the Demand.

A thing which is limited in quantity, even though its possessors do not act in concert, is still a monopolized article. But even when monopolized, a thing which is the gift of nature, and requires no labor or outlay as the condition of its existence, will, if there be competition among the holders of it, command a price only if it exist in less quantity than the demand.

If the whole land of a country were required for cultivation, all of it might yield a rent. But in no country of any extent do the wants of the population require that all the land, which is capable of cultivation, should be cultivated. The food and other agricultural produce which the people need, and which they are willing and able to pay for at a price which remunerates the grower, may always be obtained without cultivating all the land; sometimes without cultivating more than a small part of it; the more fertile lands, or those in the more convenient situations, being of course preferred. There is always, therefore, some land which can not, in existing circumstances, pay any rent; and no land ever pays rent unless, in point of fertility or situation, it belongs to those superior kinds which exist in less quantity [pg 234]than the demand—which can not be made to yield all the produce required for the community, unless on terms still less advantageous than the resort to less favored soils. (1.) The worst land which can be cultivated as a means of subsistence is that which will just replace the seed and the food of the laborers employed on it, together with what Dr. Chalmers calls their secondaries; that is, the laborers required for supplying them with tools, and with the remaining necessaries of life. Whether any given land is capable of doing more than this is not a question of political economy, but of physical fact. The supposition leaves nothing for profits, nor anything for the laborers except necessaries: the land, therefore, can only be cultivated by the laborers themselves, or else at a pecuniary loss; and, a fortiori, can not in any contingency afford a rent. (2.) The worst land which can be cultivated as an investment for capital is that which, after replacing the seed, not only feeds the agricultural laborers and their secondaries, but affords them the current rate of wages, which may extend to much more than mere necessaries, and leaves, for those who have advanced the wages of these two classes of laborers, a surplus equal to the profit they could have expected from any other employment of their capital. (3.) Whether any given land can do more than this is not merely a physical question, but depends partly on the market value of agricultural produce. What the land can do for the laborers and for the capitalist, beyond feeding all whom it directly or indirectly employs, of course depends upon what the remainder of the produce can be sold for. The higher the market value of produce, the lower are the soils to which cultivation can descend, consistently with affording to the capital employed the ordinary rate of profit.

As, however, differences of fertility slide into one another by insensible gradations; and differences of accessibility, that is, of distance from markets do the same; and since there is land so barren that it could not pay for its cultivation at any price; it is evident that, whatever the [pg 235]price may be, there must in any extensive region be some land which at that price will just pay the wages of the cultivators, and yield to the capital employed the ordinary profit, and no more. Until, therefore, the price rises higher, or until some improvement raises that particular land to a higher place in the scale of fertility, it can not pay any rent. It is evident, however, that the community needs the produce of this quality of land; since, if the lands more fertile or better situated than it could have sufficed to supply the wants of society, the price would not have risen so high as to render its cultivation profitable. This land, therefore, will be cultivated; and we may lay it down as a principle that, so long as any of the land of a country which is fit for cultivation, and not withheld from it by legal or other factitious obstacles, is not cultivated, the worst land in actual cultivation (in point of fertility and situation together) pays no rent.

§ 3. The Rent of Land is the Excess of its Return above the Return to the worst Land in Cultivation.

If, then, of the land in cultivation, the part which yields least return to the labor and capital employed on it gives only the ordinary profit of capital, without leaving anything for rent, a standard [i.e., the “margin of cultivation”] is afforded for estimating the amount of rent which will be yielded by all other land. Any land yields just as much more than the ordinary profits of stock as it yields more than what is returned by the worst land in cultivation. The surplus is what the farmer can afford to pay as rent to the landlord; and since, if he did not so pay it, he would receive more than the ordinary rate of profit, the competition of other capitalists, that competition which equalizes the profits of different capitals, will enable the landlord to appropriate it. The rent, therefore, which any land will yield, is the excess of its produce, beyond what would be returned to the same capital if employed on the worst land in cultivation.

It has been denied that there can be any land in cultivation which pays no rent, because landlords (it is contended) would not allow their land to be occupied without payment. [pg 236]Inferior land, however, does not usually occupy, without interruption, many square miles of ground; it is dispersed here and there, with patches of better land intermixed, and the same person who rents the better land obtains along with it the inferior soils which alternate with it. He pays a rent, nominally for the whole farm, but calculated on the produce of those parts alone (however small a portion of the whole) which are capable of returning more than the common rate of profit. It is thus scientifically true that the remaining parts pay no rent.

This point seems to need some illustration. Suppose that all the lands in a community are of five different grades of productiveness. When the price of agricultural produce was such that grades one, two, and three all came into cultivation, lands of poorer quality would not be cultivated. When a man rents a farm, he always gets land of varying degrees of fertility within its limits. Now, in determining what he ought to pay as rent, the farmer will agree to give that which will still leave him a profit on his working capital; if in his fields he finds land which would not enter into the question of rental, because it did not yield more than the profit on working it, after he rented the farm he would find it to his interest to cultivate it, simply because it yielded him a profit, and because he was not obliged to pay rent upon it; if required to pay rent for it, he would lose the ordinary rate of profit, would have no reason for cultivating it, of course, and would throw it out of cultivation. Moreover, suppose that lands down to grade three paid rent when A took the farm; now, if the price of produce rises slightly, grade four may pay something, but possibly not enough to warrant any rent going to a landlord. A will put capital on it for this return, but certainly not until the price warrants it; that is, not until the price will return him at least the cost of working the land, plus the profit on his outlay. But the community needed this land, or the price would not have gone up to the point which makes possible its cultivation even for a profit, without rent. There must always be somewhere some land affected in just this way.

§ 4. —Or to the Capital employed in the least advantageous Circumstances.

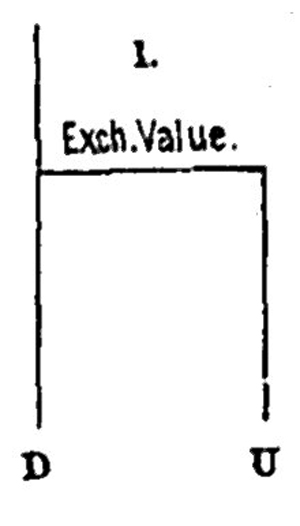

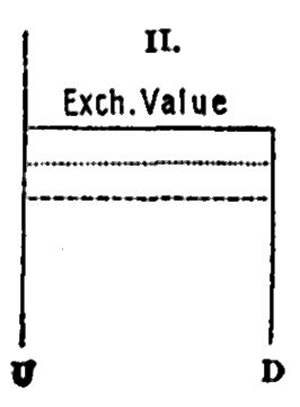

Let us, however, suppose that there were a validity in this objection, which can by no means be conceded to it; that, when the demand of the community had forced up food to such a price as would remunerate the expense of producing it from a certain quality of soil, it happened nevertheless [pg 237]that all the soil of that quality was withheld from cultivation, the increase of produce, which the wants of society required, would for the time be obtained wholly (as it always is partially), not by an extension of cultivation, but by an increased application of labor and capital to land already cultivated.

Now we have already seen that this increased application of capital, other things being unaltered, is always attended with a smaller proportional return. The rise of price enables measures to be taken for increasing the produce, which could not have been taken with profit at the previous price. The farmer uses more expensive manures, or manures land which he formerly left to nature; or procures lime or marl from a distance, as a dressing for the soil; or pulverizes or weeds it more thoroughly; or drains, irrigates, or subsoils portions of it, which at former prices would not have paid the cost of the operation; and so forth. The farmer or improver will only consider whether the outlay he makes for the purpose will be returned to him with the ordinary profit, and not whether any surplus will remain for rent. Even, therefore, if it were the fact that there is never any land taken into cultivation, for which rent, and that too of an amount worth taking into consideration, was not paid, it would be true, nevertheless, that there is always some agricultural capital which pays no rent, because it returns nothing beyond the ordinary rate of profit: this capital being the portion of capital last applied—that to which the last addition to the produce was due; or (to express the essentials of the case in one phrase) that which is applied in the least favorable circumstances. But the same amount of demand and the same price, which enable this least productive portion of capital barely to replace itself with the ordinary profit, enable every other portion to yield a surplus proportioned to the advantage it possesses. And this surplus it is which competition enables the landlord to appropriate.

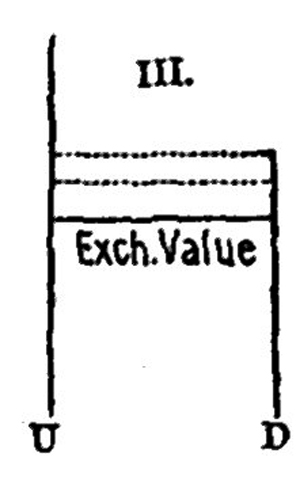

If land were all occupied, and of only one grade, the first installment of labor and capital produced, we will say, twenty bushels of wheat; when the price of wheat rose, and it became [pg 238]profitable to resort to greater expense on the soil, a second installment of the same amount of labor and capital when applied, however, only yielded fifteen bushels more; a third, ten bushels more; and a fourth, five bushels more. The soil now gives fifty bushels only under the highest pressure. But, if it was profitable to invest the same installment of labor and capital simply for the five bushels that at first had received a return of twenty bushels, the price must have gone up so that five bushels should sell for as much as the twenty did formerly; so, mutatis mutandis, of installments second and third. So that if the demand is such as to require all of the fifty bushels, the agricultural capital which produced the five bushels will be the standard according to which the rent of the capital, which grew twenty, fifteen, and ten bushels respectively, is measured. The principle is exactly the same as if equal installments of capital and labor were invested on four different grades of land returning twenty, fifteen, ten, and five bushels for each installment. Or, as if in the table on page 240, A, B, C, and D each represented different installments of the same amount of labor and capital put upon the same spot of ground, instead of being, as there, put upon different grades of land.

The rent of all land is measured by the excess of the return to the whole capital employed on it above what is necessary to replace the capital with the ordinary rate of profit, or, in other words, above what the same capital would yield if it were all employed in as disadvantageous circumstances as the least productive portion of it: whether that least productive portion of capital is rendered so by being employed on the worst soil, or by being expended in extorting more produce from land which already yielded as much as it could be made to part with on easier terms.

It will be true that the farmer requires the ordinary rate of profit on the whole of his capital; that whatever it returns to him beyond this he is obliged to pay to the landlord, but will not consent to pay more; that there is a portion of capital applied to agriculture in such circumstances of productiveness as to yield only the ordinary profits; and that the difference between the produce of this and of any other capital of similar amount is the measure of the tribute which that other capital can and will pay, under the name of rent, to the landlord. This constitutes a law of rent, as near the [pg 239]truth as such a law can possibly be; though of course modified or disturbed, in individual cases, by pending contracts, individual miscalculations, the influence of habit, and even the particular feelings and dispositions of the persons concerned.

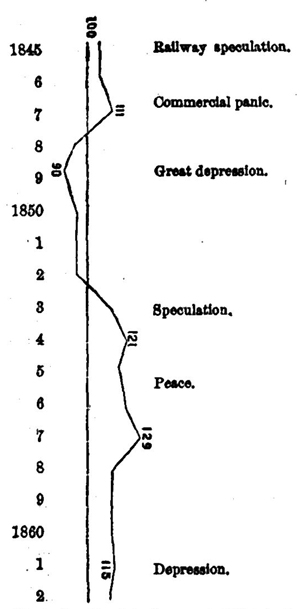

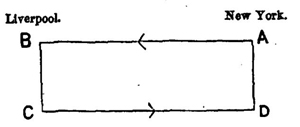

The law of rent, in the economic sense, operates in the United States as truly as elsewhere, although there is no separate class of landlords here. With us, almost all land is owned by the cultivator; so that two functions, those of the landlord and farmer, are both united in one person. Although one payment is made, it is still just as distinctly made up of two parts, one of which is a payment to the owner for the superior quality of his soil, and the other a payment (to the same person, if the owner is the cultivator) of profit on the farmer's working capital. Land which in the United States will only return enough to pay a profit on this capital can not pay any rent. And land which can pay more than a profit on this working capital, returns that excess as rent, even if the farmer is also the owner and landlord. The principle which regulates the amount of that excess—which is the essential point—is the principle which determines the amount of economic rent, and it holds true in the United States or Finland, provided only that different grades of land are called into cultivation. The governing principle is the same, no matter whether a payment is made to one man as profit and to another as rent, or whether the two payments are made to the same man in two capacities. It has been urged that the law of rent does not hold in the United States, because “the price of grain and other agricultural produce has not risen in proportion to the increase of our numbers, as it ought to have done if Ricardo's theory were true, but has fallen, since 1830, though since that time our population has been more than tripled.”181 This overlooks the fact that we have not even yet taken up all our best agricultural lands, so that for some products the law of diminishing productiveness has not yet shown itself. The reason is, that the extension of our railway system has only of late years brought the really good grain-lands into cultivation. The fact that there has been no rise in agricultural products is due to the enormous extent of marvelously fertile grain-lands in the West, and to the cheapness of transportation from those districts to the seaboard.

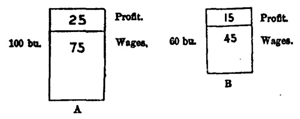

For a general understanding of the law of rent the following table will show how, under constant increase of population (represented by four different advances of population, in the [pg 240]first column), first the best and then the poorer lands are brought into cultivation. We will suppose (1) that the most fertile land, A, at first pays no rent; then (2), when more food is wanted than land A can supply, it will be profitable to till land B, but which, as yet, pays no rent. But if eighteen bushels are a sufficient return to a given amount of labor and capital, then when an equal amount of labor and capital engaged on A returns twenty-four bushels, six of that are beyond the ordinary profit, and form the rent on land A, and so on; C will next be the line of comparison, and then D; as the poorer soils are cultivated, the rent of A increases:

Population Increase. / A -- / B -- / C -- / D / --

-- / 24 bushels -- / 18 bushels / -- / 12 bushels -- / 6 bushels / --

-- / Total product / Rent in Bushels / Total product / Rent in Bushels / Total product / Rent in Bushels Total product / Rent in Bushels

I. / 24 / 0 / .. / .. / .. / .. / .. / ..

II. / 24 / 6 / 18 / 0 / .. / .. / .. / ..

III. / 24 / 12 / 18 / 6 / 12 / 0 / .. / ..

IV. / 24 / 18 / 18 / 12 / 12 / 6 /6 / 0

§ 5. Opposing Views of the Law of Rent.

Under the name of rent, many payments are commonly included, which are not a remuneration for the original powers of the land itself, but for capital expended on it. The buildings are as distinct a thing from the farm as the stock or the timber on it; and what is paid for them can no more be called rent of land than a payment for cattle would be, if it were the custom that the landlord should stock the farm for the tenant. The buildings, like the cattle, are not land, but capital, regularly consumed and reproduced; and all payments made in consideration for them are properly interest.

But with regard to capital actually sunk in improvements, and not requiring periodical renewal, but spent once for all in giving the land a permanent increase of productiveness, it appears to me that the return made to such capital loses altogether the character of profits, and is governed by the principles of rent. It is true that a landlord will not expend capital in improving his estate unless he expects from the improvement an increase of income surpassing the interest [pg 241]of his outlay. Prospectively, this increase of income may be regarded as profit; but, when the expense has been incurred and the improvement made, the rent of the improved land is governed by the same rules as that of the unimproved.

Mr. Carey (as well as Bastiat) has declared that there is a law of increasing returns from land. He points out that everything now existing could be reproduced to-day at a less cost than that involved in its original production, owing to our advance in skill, knowledge, and all the arts of production; that, for example, it costs less to make an axe now than it did five hundred years ago; so also with a farm, since a farm of a given amount of productiveness can be brought into cultivation at less cost to-day than that originally spent upon it. The gain of society has, we all admit, been such that we produce almost everything at a less cost now than long ago; but to class a farm and an axe together overlooks, in the most remarkable way, the fact that land can not be created by labor and capital, while axes can, and that too indefinitely. Nor can the produce from the land be increased indefinitely at a diminishing cost. This is sometimes denied by the appeal to facts: “It can be abundantly proved that, if we take any two periods sufficiently distant to afford a fair test, whether fifty or one hundred or five hundred years, the production of the land relatively to the labor employed upon it has progressively become greater and greater.”182 But this does not prove that an existing tendency to diminishing returns has not been more than offset by the progress of the arts and improvements. “The advance of a ship against wind and tide is [no] proof that there is no wind and tide.”

In a work entitled “The Past, the Present, and the Future,” Mr. Carey takes [a] ground of objection to the Ricardo theory of rent, namely, that in point of historical fact the lands first brought under cultivation are not the most fertile, but the barren lands. “We find the settler invariably occupying the high and thin lands requiring little clearing and no drainage. With the growth of population and wealth, other soils yielding a larger return to labor are always brought into activity, with a constantly increasing return to the labor expended upon them.”

In whatever order the lands come into cultivation, those [pg 242]which when cultivated yield the least return, in proportion to the labor required for their culture, will always regulate the price of agricultural produce; and all other lands will pay a rent simply equivalent to the excess of their produce over this minimum. Whatever unguarded expressions may have been occasionally used in describing the law of rent, these two propositions are all that was ever intended by it. If, indeed, Mr. Carey could show that the return to labor from the land, agricultural skill and science being supposed the same, is not a diminishing return, he would overthrow a principle much more fundamental than any law of rent. But in this he has wholly failed.

Another objection taken against the law of diminishing returns, and so against the law of rent, is that the potential increase of food, e.g., of a grain of wheat, is far greater than that of man.183 No one disputes the fact that one grain of wheat can reproduce itself more times than man, and that too in a geometric increase; but not without land. A grain of wheat needs land in which it can multiply itself, and this necessary element of its increase is limited; and it is the very thing which limits the multiplication of the grains of wheat. On the same piece of land, one can not get more than what comes from one act of reproduction in the grain. If one grain produces 100 of its kind, doubling the capital will not repeatedly cause a geometric increase in the ratio of reproduction of each grain on this same land, so that one grain, by one process, produces of its kind 200, 400, 800, or 1,600, because you can not multiply the land in any such ratio as would accompany this potential reduplication of the grain. This objection would not seem worth answering, were it not that it furnishes some difficulty to really honest inquirers.

Others, again, allege as an objection against Ricardo, that if all land were of equal fertility it might still yield a rent. But Ricardo says precisely the same. It is also distinctly a portion of Ricardo's doctrine that, even apart from differences of situation, the land of a country supposed to be of uniform fertility would, all of it, on a certain supposition, pay rent, namely, if the demand of the community required [pg 243]that it should all be cultivated, and cultivated beyond the point at which a further application of capital begins to be attended with a smaller proportional return.

This is simply the question, before discussed, whether, if only one class of land were cultivated, some agricultural capital would pay rent or not. It all depends on the fact whether population—and so the demand for food—has increased to the point where it calls out a recognition of the diminishing productiveness of the soil. In that case different capitals would be invested, so that there would be different returns to the same amount of capital; and the prior or more advantageous investments of capital on the land would yield more than the ordinary rate of profit, which could be claimed as rent.

A. L. Perry184 admits the law of diminishing returns, but holds that, “as land is capital, and as every form of capital may be loaned or rented, and thus become fruitful in the hands of another, the rent of land does not differ essentially in its nature from the rent of buildings in cities, or from the interest of money.” Henry George admits Ricardo's law of rent to its full extent, but very curiously says: “Irrespective of the increase of population, the effect of improvements in methods of production and exchange is to increase rent.... The effect of labor-saving improvements will be to increase the production of wealth. Now, for the production of wealth, two things are required, labor and land. Therefore, the effect of labor-saving improvements will be to extend the demand for land, and, wherever the limit of the quality of land in use is reached, to bring into cultivation lands of less natural productiveness, or to extend cultivation on the same lands to a point of lower natural productiveness. And thus, while the primary effect of labor-saving improvements is to increase the power of labor, the secondary effect is to extend cultivation, and, where this lowers the margin of cultivation, to increase rent.”185 Francis Bowen186 rejects Ricardo's law, and says, “Rent depends, not on the increase, but on the distribution, of the population”—asserting that the existence of large cities and towns determines the amount of rent paid by neighboring land.187

§ 6. Rent does not enter into the Cost of Production of Agricultural Produce.

Rent does not really form any part of the expenses of [agricultural] production, or of the advances of the capitalist. The grounds on which this assertion was made are now apparent. It is true that all tenant-farmers, and many other classes of producers, pay rent. But we have now seen that whoever cultivates land, paying a rent for it, gets in return for his rent an instrument of superior power to other instruments of the same kind for which no rent is paid. The superiority of the instrument is in exact proportion to the rent paid for it. If a few persons had steam-engines of superior power to all others in existence, but limited by physical laws to a number short of the demand, the rent which a manufacturer would be willing to pay for one of these steam-engines could not be looked upon as an addition to his outlay, because by the use of it he would save in his other expenses the equivalent of what it cost him: without it he could not do the same quantity of work, unless at an additional expense equal to the rent. The same thing is true of land. The real expenses of production are those incurred on the worst land, or by the capital employed in the least favorable circumstances. This land or capital pays, as we have seen, no rent, but the expenses to which it is subject cause all other land or agricultural capital to be subjected to an equivalent expense in the form of rent. Whoever does pay rent gets back its full value in extra advantages, and the rent which he pays does not place him in a worse position than, but only in the same position as, his fellow-producer who pays no rent, but whose instrument is one of inferior efficiency.

Soils are of every grade: some, which if cultivated, might replace the capital, but give no profit; some give a slight but not an ordinary profit; some, the ordinary profit. That is, “there is a point up to which it is profitable to cultivate, and beyond which it is not profitable to cultivate. The price of corn will not, for any long time, remain at a higher rate than is sufficient to cover with ordinary profit the cost of that portion of the general crop which is raised at greatest expense.”188 For similar reasons the price will not remain at a [pg 245]lower rate. If, then, the cost of production of grain is determined by that land which replaces the capital, yields only the ordinary profit, and pays no rent, rent forms no part of this cost, since that land does not and can not pay any rent. McLeod,189 however, says it is not the cost of production which regulates the value of which regulates the cost.