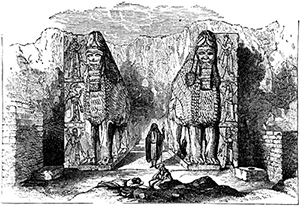

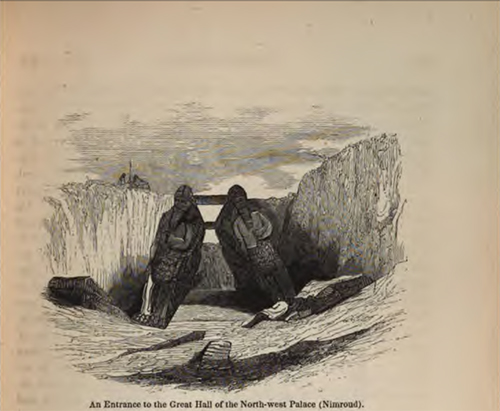

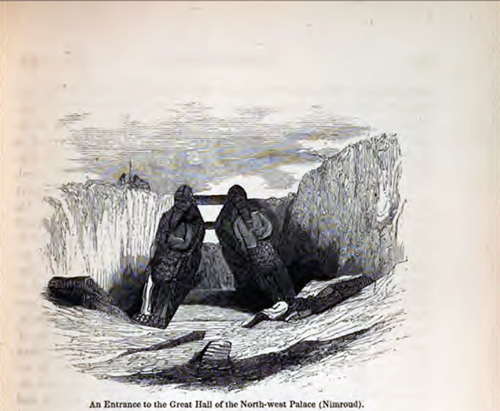

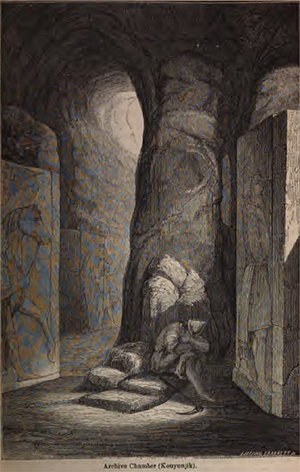

The newly discovered chamber was part of the north-west palace, and adjoining a room previously explored.[72] Its only entrance was to the west, and almost on the edge of the mound. It must, consequently, have opened upon a gallery or terrace running along the river front of the building. The walls were of sun-dried brick, panelled round the bottom with large burnt bricks, about three feet high, placed one against the other. They were coated with bitumen, and, like those forming the pavement, were inscribed with the name and usual titles of the royal founder of the building. In one corner, and partly in a kind of recess, was a well, the mouth of which was formed by brickwork about three feet high. Its sides were also bricked down to the conglomerate rock, and holes had been left at regular intervals for descent. When first discovered it was choked with earth. The workmen emptied it until they came, at the depth of nearly sixty feet, to brackish water.[73]

[Pg 151]The first objects found in this chamber were two plain copper vessels or caldrons, about 2½ feet in diameter, and 3 feet deep, resting upon a stand of brickwork, with their mouths closed by large tiles. Near them was a copper jar, which fell to pieces almost as soon as uncovered. Several vases of the same metal, though smaller in size, had been dug out of other parts of the ruins; but they were empty, whilst those I am describing were filled with curious relics. I first took out a number of small bronze bells[74] with iron tongues, and various small copper ornaments, some suspended to wires. With them were a quantity of tapering bronze rods, bent into a hook, and ending in a kind of lip. Beneath were several bronze cups and dishes, which I succeeded in removing entire. Scattered in the earth amongst these objects were several hundred studs and buttons in mother of pearl and ivory, with many small rosettes in metal.

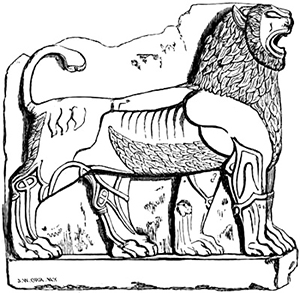

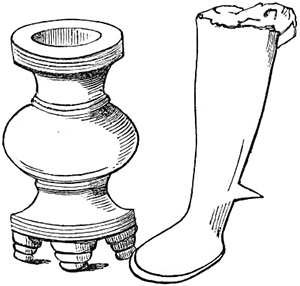

Feet of Tripods in Bronze and Iron.

All the objects contained in these caldrons, with the exception of the cups and dishes, were probably ornaments of horse and chariot furniture.

Beneath the caldrons were heaped[Pg 152] lions’ and bulls’ feet of bronze; and the remains of iron rings and bars, probably parts of tripods, or stands, for supporting vessels and bowls; which, as the iron had rusted away, had fallen to pieces, leaving such parts entire as were in the more durable metal.

Two other caldrons, found further within the chamber, contained, besides several plates and dishes, four crown shaped bronze ornaments, perhaps belonging to a throne or couch; two long, ornamented bands of copper, rounded at both ends, apparently belts, such as were worn by warriors in armour; a grotesque head in bronze, probably the top of a mace; a metal wine-strainer of elegant shape; various metal vessels of peculiar form, and a bronze ornament, probably the handle of a dish or vase.

Eight more caldrons and jars were found in other parts of the chamber. One contained ashes and bones, the rest were empty. Some of the larger vessels were crushed almost flat, probably by the falling in of the upper part of the building.

With the caldrons were discovered two circular flat vessels, nearly six feet in diameter, and about two feet deep, which I can only compare with the brazen sea that stood in the temple of Solomon.[75]

Caldrons are frequently represented as part of the spoil and tribute, in the sculptures of Nimroud and Kouyunjik. They were so much valued by the ancients that, it appears from the Homeric poems, they were given as prizes at public games, and were considered amongst the most precious objects that could be carried away from a captured city. They were frequently embossed with[Pg 153] flowers and other ornaments. Homer declares one so adorned to be worth an ox.[76]

Behind the caldrons was a heap of curious and interesting objects. In one place were piled without order, one above the other, bronze cups, bowls, and dishes of various sizes and shapes. The upper vessels having been most exposed to damp, the metal had been eaten away by rust, and was crumbling into fragments, or into a green powder. As they were cleared away, more perfect specimens were taken out, until, near the pavement of the chamber, some were found almost entire. Many of the bowls and plates fitted so closely, one within the other, that they have only been detached in England. It required the greatest care and patience to separate them from the tenacious soil in which they were embedded.

Although a green crystaline deposit, arising from the decomposition of the metal, encrusted all the vessels, I could distinguish upon many of them traces of embossed and engraved ornaments. Since they have been in England they have been carefully and skilfully cleaned, and the very beautiful and elaborate designs upon them brought to light.

The bronze objects thus discovered may be classed under four heads—dishes with handles, plates, deep bowls, and cups. Some are plain, others have a simple rosette, scarab, or star in the centre, and many are most elaborately ornamented with the figures of men and animals, and with elegant fancy designs, either embossed or incised. The inside, and not the outside, of these vessels is ornamented. The embossed figures have been raised in the metal by a blunt instrument, three or four strokes[Pg 154] of which in many instances very ingeniously produce the image of an animal. Even those ornaments which are not embossed but incised, appear to have been formed by a similar process, except that the punch was applied on the inside. The tool of the graver has been sparingly used.

The most interesting dishes in the collection brought to England are:—

No. 1., with moving circular handle (the handle wanting), secured by three bosses; diameter 10¾ inches, depth 2¼ inches; divided into two friezes surrounding a circular medallion containing a male deity with bull’s ears (?) and hair in ample curls[77], wearing bracelets and a necklace of an Egyptian character, and a short tunic; the arms crossed, and the hands held by two Egyptians (?), who place their other hands on the head of the centre figure. The inner frieze contains horsemen draped as Egyptians, galloping round in pairs; the outer, figures also wearing the Egyptian “shenti” or tunic, hunting lions on horseback, on foot, and in chariots. The hair of these figures is dressed after a fashion, which prevailed in Egypt from the ninth to the eighth century b. c. Each frieze is separated by a band of guilloche ornament.

No. 2., diameter 10½ inches, having a low rim, partly destroyed; ornamented with an embossed rosette of elegant shape, surrounded by three friezes of animals in high relief, divided by a guilloche band. The outer frieze contains twelve walking bulls, designed with considerable spirit; between each is a dwarf shrub or tree. The second frieze has a bull, a winged griffin, an ibex, and a gazelle, walking one behind the other, and the same animals[Pg 155] seized by leopards or lions, in all fourteen figures. The inner frieze contains twelve gazelles. The handle is formed by a plain movable ring. The ornaments on this dish, as well as the design, are of an Assyrian character.

No. 3., diameter 10¾ inches, and 1½ inch deep, with a raised star in the centre; the handle formed by two rings, working in sockets fastened to a rim, running about one-third round the margin, and secured by five nails or bosses; four bands of embossed ornaments in low relief round the centre, the outer band consisting of alternate standing bulls and crouching lions, Assyrian in character and treatment; the others, of an elegant pattern, slightly varied from the usual Assyrian border by the introduction of a fanlike flower in the place of the tulip.

Other dishes were found still better preserved than those just described, but perfectly plain, or having only a star, more or less elaborate, embossed or engraved in the centre. Many fragments were also discovered with elegant handles, some formed by the figures of rams and bulls.

Of the plates the most remarkable are:—

No. 1., shallow, and 8¾ inches in diameter, the centre slightly raised and incised with a star and five bands of tulip-shaped ornaments; the rest occupied by four groups, each consisting of two winged hawk-headed sphinxes, wearing the “pshent,” or crown of the upper and lower country of Egypt; one paw raised, and resting upon the head of a man kneeling on one knee, and lifting his hands in the act of adoration. Between the sphinxes, on a column in the form of a papyrus-sceptre, is the bust of a figure wearing on his head the sun’s disc, with the uræi serpents, a collar round the neck, and four feathers; above are two winged globes with the asps, and a row of birds. Each group is inclosed by two columns with capitals[Pg 156] in the form of the Assyrian tulip ornament, and is separated from that adjoining by a scarab with out-spread wings, raising the globe with its fore feet, and resting with its hind on a papyrus-sceptre pillar. This plate is in good preservation, having been found at the very bottom of a heap of similar relics.

No. 2., depth, 1¾ in.; diameter, 9⅛ in., with a broad, raised rim, like that of a soup plate, embossed with figures of greyhounds pursuing a hare. The centre contains a frieze in high relief, representing combats between men and lions, and a smaller border of gazelles, between guilloche bands, encircling an embossed star. In this very fine specimen, although the costumes of the figures are Egyptian in character, the treatment and design are Assyrian.

No. 3., shallow; 9½ inches diameter; an oval in the centre, covered with dotted lozenges, and set with nine silver bosses, probably intended to represent a lake or valley, surrounded by four groups of hills, each with three crests in high relief, on which are incised in outline trees and stags, wild goats, bears, and leopards. On the sides of the hills, in relief, are similar figures of animals. The outer rim is incised with trees and deer. The workmanship of this specimen is Assyrian, and very minute and curious.

No. 4., diameter, 7¼ inches, the centre raised, and containing an eight-rayed star, with smaller stars between each ray, encircled by a guilloche band. The remainder of the plate is divided into eight compartments, by eight double-faced figures of Egyptian character in high relief; between each figure are five rows of animals, inclosed by guilloche bands; the first three consisting of stags and hinds, the fourth of lions, and the fifth of hares, each compartment containing thirteen figures. A very beautiful specimen, unfortunately much injured.

[Pg 157]No. 5., diameter, 8¾ inches; depth, 1¼ inch. The embossings and ornaments on this plate are of an Egyptian character. The centre consists of four heads of the cow-eared goddess Athor (?), forming, with lines of bosses, an eight-rayed star, surrounded by hills, indicated as in plate No. 3., but filled in with rosettes and other ornaments. Between the hills are incised animals and trees. A border of figures, almost purely Egyptian, but unfortunately only in part preserved, encircles the plate; the first remaining group is that of a man seated on a throne, beneath an ornamented arch, with the Egyptian Baal, represented as on the coins of Cossura, standing full face; to the right of this figure is a square ornament with pendants (resembling a sealed document), and beneath it the crux ansata or Egyptian symbol of life. The next group is that of a warrior in Egyptian attire, holding a mace in his right hand, and in his left a bow and arrow, with the hair of a captive of smaller proportions, who crouches before him. The next group represents the Egyptian Baal (?), with a lion’s skin round his body, and plumes on his head, having on each side an Egyptian figure wearing the “shent,” or short tunic, carrying a bow, and plucking the plumes from the head of the god, perhaps symbolical of the victory of Horus over Typhon. The Egyptian god Amon, bearing a bird in one hand and a falchion in the other, with female figures similar to that last described, appears to form the next group; but unfortunately this part of the plate has been nearly destroyed: the whole border, however, appears to have represented a mixture of religious and historical scenes.

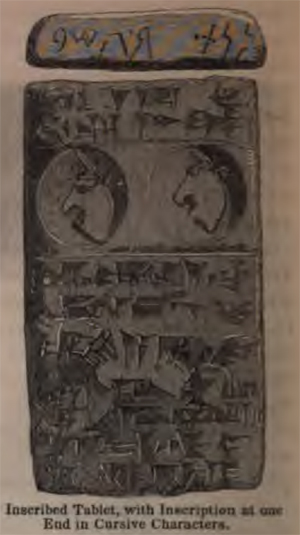

No. 6., diameter, 6 in.; depth, 1½ in.; a projecting rim, ornamented with figures of vultures with out-spread wings; an embossed rosette, encircled by two rows of fan-shaped flowers and guilloche bands, occupies a raised[Pg 158] centre, which is surrounded by a frieze, consisting of groups of two vultures devouring a hare. A highly finished and very beautiful specimen. On the back of this plate are five letters, either in the Phœnician or Assyrian cursive character.

Nos. 7. and 8.; covered with groups of small stags, surrounding an elaborate star, one plate containing above 600 figures; the animals are formed by three blows from a blunt instrument or punch. These plates are ornamented with small bosses of silver and gold let into the copper.

No. 9., diameter, 7⅝ inches; depth, 1½ inch, of fine workmanship; the centre formed by an incised star, surrounded by guilloche and tulip bands. Four groups on the sides representing a lion, lurking amongst papyri or reeds, and about to spring on a bull.

No. 10., diameter 7½ inches. In the centre a winged scarab raising the disc of the sun, surrounded by guilloche and tulip bands, and by a double frieze, the inner consisting of trees, deer, winged uræi, sphinxes, and papyrus plants; the outer, of winged scarabs, flying serpents, deer, and trees, all incised.

The plates above described are the most interesting specimens brought to this country: there are others, indeed, scarcely less remarkable for beauty of workmanship, or, when plain or ornamented with a simple star in the centre, for elegance of form. Of the seventeen deep bowls discovered, only three have embossings, sufficiently well preserved, to be described; the greater part appear to be perfectly plain. The most remarkable is 8½ inches in diameter, and 3¾ inches deep, and has at the bottom, in the centre, an embossed star, surrounded by a rosette, and on the sides a hunting scene in bold relief.

A second, 7½ inches in diameter, and 3¾ inches deep,[Pg 159] has in the centre a medallion similar to that in the one last described, and on the sides, in very high relief, two lions and two sphinxes of Egyptian character, wearing a collar, feathers, and housings, and a head-dress formed by a disc with two uræi. Both bowls are remarkable for the boldness of the relief and the archaic treatment of the figures, in this respect resembling the ivories previously discovered at Nimroud. They forcibly call to mind the early remains of Greece, and especially the metal work, and painted pottery found in very ancient tombs in Etruria, which they so closely resemble not only in design but in subject, the same mythic animals and the same ornaments being introduced, that we cannot but attribute to both the same origin. The third, 7¾ inches in diameter, and 2½ inches deep, has in the centre a star formed by the Egyptian hawk of the sun, bearing the disc, and having at its side a whip, between two rays ending in lotus flowers; on the sides are embossed figures of wild goats, lotus-shaped shrubs, and dwarf trees of peculiar form.

Of the cups the most remarkable are:—

No. 1., diameter 5⅝ inches, and 2¼ inches deep, very elaborately ornamented with figures of animals, interlaced and grouped together in singular confusion, covering the whole inner surface; apparently representing a combat between griffins and lions; a very curious and interesting specimen, not unlike some of the Italian chasing of the cinque cento. No. 2., a fragment, embossed with the figures of lions and bulls, of very fine workmanship.

Of the remaining cups many are plain but of elegant shape, one or two are ribbed, and some have simply an embossed star in the centre.

About 150 bronze vessels discovered in this chamber are now in the British Museum, without including numerous fragments, which, although showing traces of [Pg 160]ornament, are too far destroyed by decomposition to be cleaned.

The metal of the dishes, bowls, and rings, has been carefully analysed, and has been found to contain one part of tin to ten of copper, being exactly the relative proportions of the best ancient and modern bronze. The bells, however, have fourteen per cent. of tin, showing that the Assyrians were well aware of the effect produced by changing the proportions of the metals. These two facts show the advance made by them in the metallurgic art.

The effect of age and decay has been to cover the surface of all these bronze objects with a coating of beautiful crystals of malachite, beneath which the component substances have been converted into suboxide of copper and peroxide of tin, leaving in many instances no traces whatever of the metals.

It would appear that the Assyrians were unable to give elegant forms or a pleasing appearance to objects in iron alone, and that consequently they frequently overlaid that metal with bronze, either entirely, or partially, by way of ornament. The feet of the ring tripods previously described, furnish highly interesting specimens of this process, and prove the progress made by the Assyrians in it. The iron inclosed within the copper has not been exposed to the same decay as that detached from it, and will still take a polish.

The tin was probably obtained from Phœnicia; and consequently that used in the bronzes of the British Museum may actually have been exported, nearly three thousand years ago, from the British Isles! We find the Assyrians and Babylonians making an extensive use of this metal, which was probably one of the chief articles of trade supplied by the cities of the Syrian coast, whose[Pg 161] seamen sought for it on the distant shores of the Atlantic.

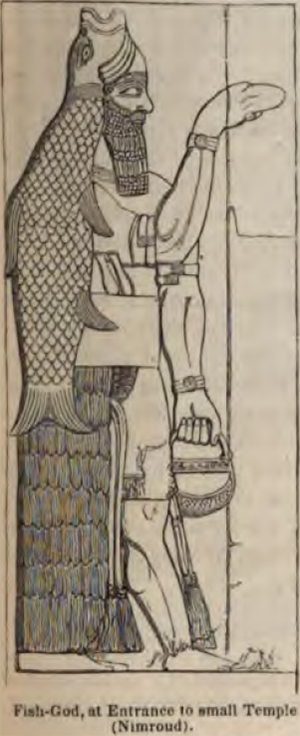

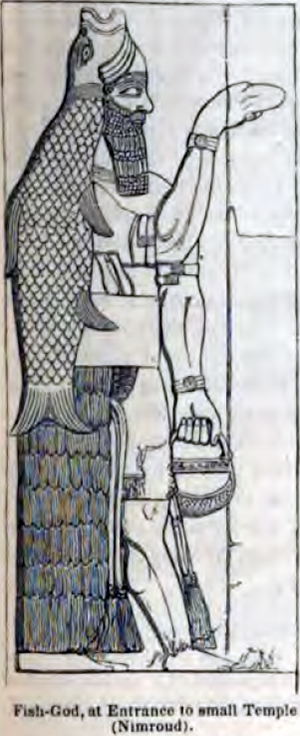

The embossed and engraved vessels from Nimroud afford many interesting illustrations of the progress made by the ancients in metallurgy. From the Egyptian character of the designs, and especially of the drapery of the figures, in several of the specimens, it may be inferred that some of them were not Assyrian, but had been brought from a foreign people. As in the ivories, however, the workmanship, subjects, and mode of treatment are more Assyrian than Egyptian, and seem to show that the artist either copied from Egyptian models, or was a native of a country under the influence of the arts and taste of Egypt. The Sidonians, and other inhabitants of the Phœnician coast, were the most renowned workers in metal of the ancient world. In the Homeric poems they are frequently mentioned as the artificers who fashioned and embossed metal cups and bowls, and Solomon sought cunning men from Tyre to make the gold and brazen utensils for his temple and palaces.[78] It is, therefore, not impossible that the vessels discovered at Nimroud were the work of Phœnician artists, brought expressly from Tyre, or carried away amongst the captives when their cities were taken by the Assyrians, who, we know from many passages in the Bible[79], always secured the smiths and artisans, and placed them in their own immediate dominions. They may have been used for sacrificial purposes, at royal banquets, or when the king performed certain religious ceremonies, for in the bas-reliefs he is frequently represented on such occasions with a cup or bowl in his hand; or they may have formed part of the spoil of some Syrian nation,[Pg 162] placed in a temple at Nineveh, as the holy utensils of the Jews, after the destruction of the sanctuary, were kept in the temple of Babylon.[80] It is not, indeed, impossible, that some of them may have been actually brought from the cities round Jerusalem by Sennacherib himself, or from Samaria by Shalmaneser or Sargon, who, we find, inhabited the palace at Nimroud, and of whom several relics have already been discovered in the ruins.

Around the vessels I have described were heaped arms, remains of armour, iron instruments, glass bowls, and various objects in ivory and bronze. The arms consisted of swords, daggers, shields, and the heads of spears and arrows, which being chiefly of iron fell to pieces almost as soon as exposed to the air. The shields are of bronze, and circular, the rim bending inwards, and forming a deep groove round the edge. The handles are of iron, and fastened by six bosses or nails, the heads of which form an ornament on the outer face of the shield.[81] The diameter of the largest and most perfect is two feet six inches. Although their weight must have impeded the movements of an armed warrior, the Assyrian spearmen are constantly represented in the bas-reliefs with[Pg 163] them. Such, too, were probably the bucklers that Solomon hung on his towers.[82]

A number of thin iron rods, adhering together in bundles, were found amongst the arms. They may have been the shafts of arrows, which, it has been conjectured from several passages in the Old Testament, were sometimes of burnished metal. To “make bright the arrows”[83] may, however, only allude to the head fastened to a reed, or shaft of some light wood. The armour consisted of parts of breast-plates (?) and of other fragments, embossed with figures and ornaments.

Amongst the iron instruments were the head of a pick, a double-handled saw (about 3 feet 6 inches in length), several objects resembling the heads of sledge-hammers, and a large blunt spear-head, such as we find from the sculptures were used during sieges to force stones from the walls of besieged cities.

The most interesting of the ivory relics were, a carved staff, perhaps a royal sceptre, part of which has been preserved, although in the last stage of decay; and several entire elephants’ tusks, the largest being about 2 feet 5 inches long.

The ivory could with difficulty be detached from the earth in which it was imbedded. It fell to small fragments, and even to dust, almost as soon as exposed to the air. I have described elsewhere[84] the frequent use of ivory for the adornment of ancient Eastern palaces and temples, as well as for thrones and furniture. Ezekiel includes “horns of ivory” amongst the objects brought to Tyre from Dedan, and the Assyrians may have obtained[Pg 164] their supplies from the same country, which some believe to have been in the Persian Gulf.[85]

Amongst various small objects in bronze were two cubes, each having on one face the figure of a scarab with outstretched wings, inlaid in gold; very interesting specimens, and probably amongst the earliest known, of an art carried in modern times to great perfection in the East.

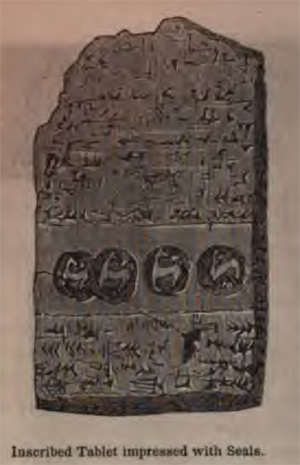

Two entire glass bowls, with fragments of others, were also found in this chamber; the glass, like all that from the ruins, is covered with pearly scales, which, on being removed, leave prismatic opal-like colors of the greatest brilliancy, showing, under different lights, the most varied and beautiful tints. On this highly interesting relic is the name of Sargon, with his title of king of Assyria, in cuneiform characters, and the figure of a lion. We are, therefore, able to fix its date to the latter part of the seventh century b. c. It is, consequently, the most ancient known specimen of transparent glass, none from Egypt being, it is believed, earlier than the time of the Psamettici (the end of the sixth or beginning of the fifth century b. c.). Opaque colored glass was, however, manufactured at a much earlier period, and some exists of the fifteenth century b. c. The Sargon vase was blown in one solid piece, and then shaped and hollowed out by a turning-machine, of which the marks are still plainly visible. With it were found, it will be remembered, two larger vases in white alabaster, inscribed with the name of the same king. They were all probably used for holding some ointment or cosmetic.[86]

With the glass bowls was discovered a rock-crystal[Pg 165] lens, with opposite convex and plane faces. Its properties could scarcely have been unknown to the Assyrians, and we have consequently the earliest specimen of a magnifying and burning-glass. It was buried beneath a heap of fragments of beautiful blue opaque glass, apparently the enamel of some object in ivory or wood, which had perished.

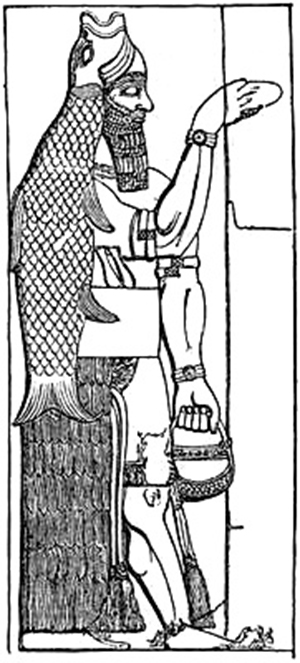

In the further corner of the chamber, to the left hand, stood the royal throne. Although it was utterly impossible, from the complete state of decay of the materials, to preserve any part of it entire, I was able, by carefully removing the earth, to ascertain that it resembled in shape the chair of state of the king, as seen in the sculptures of Kouyunjik and Khorsabad, and particularly that represented in the bas-relief already described, of Sennacherib receiving the captives and spoil, after the conquest of the city of Lachish.[87] With the exception of the legs, which appear to have been partly of ivory, it was of wood, cased or overlaid with bronze, as the throne of Solomon was of ivory, overlaid with gold.[88] The metal was most elaborately engraved and embossed with symbolical figures and ornaments, like those embroidered on the robes of the early Nimroud king, such as winged deities struggling with griffins, mythic animals, men before the sacred tree, and the winged lion and bull. As the woodwork over which the bronze was fastened by means of small nails of the same material, had rotted away, the throne fell to pieces, but the metal casing was partly preserved. The legs were adorned with lion’s paws resting on a pine-shaped ornament, like the thrones of the later Assyrian[Pg 166] sculptures, and stood on a bronze base. A rod with loose rings, to which was once hung embroidered drapery, or some rich stuff, appears to have belonged to the back of the chair, or to a frame-work raised above or behind it.

In front of the throne was the foot-stool, also of wood overlaid with embossed metal, and adorned with the heads of rams or bulls. The feet ended in lion’s paws and pine cones, like those of the throne. The two pieces of furniture may have been placed together in a temple as an offering to the gods, as Midas placed his throne in the temple of Delphi.[89] The ornaments on them were so purely Assyrian, that there can be little doubt of their having been expressly made for the Assyrian king, and not having been the spoil of some foreign nation.

Such, with an alabaster jar, and a few other objects in metal, were the relics found in the newly-opened room. After the examination I had made of the building during my former excavations, this accidental discovery proves that other treasures may still exist in the mound of Nimroud, and increases my regret that means were not at my command to remove the rubbish from the centre of the other chambers in the palace.